Cervical Ripening with an Osmotic Dilator (Dilapan-S) in Term Pregnancies

J. T. Maier1*, E. Schalinski1, U. Gauger2, L. Hellmeyer1

Affiliation

- 1Department of gynecology and obstetrics, Vivantes Klinikum im Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany

- 2Institute for medical statistics, Berlin, Germany

Corresponding Author

Josefine Maier, Department of gynecology and obstetrics, Vivantes Klinikum im Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany. E-mail: josefine.maier@googlemail.com

Citation

Maier, J.T., et al. Cervical Ripening with an Osmotic Dilator (Dilapan- S) in Term Pregnancies – An Observational Study. J Gynecol Neonatal Biol 1(2): 1- 6.

Copy rights

© 2015 Maier, J.T. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Mechanical cervical ripening; Induction of labor; Vaginal birth after cesarean section (VBAC); Prolonged pregnancy; Dilapan-S; Dilasoft; Bishop score; Dinoprostone; Minprostin; Misoprostol; Prepidil; Oxytocin; Maternal age

Abstract

Objective: The procedure of labor induction becomes increasingly important as the number of pregnancies requiring induction raises in the Western countries due to multiple reasons. In addition, a growing number of patients are aiming to achieve vaginal birth after cesarean section (VBAC). No pharmacological agent is licensed in this group of patients. A newly developed hydrophilic agent (Dilapan-S) is now available for cervical ripening, and is indicated also for patients with a previous cesarean section.

Methods: Observational, non-interventional study in a tertiary perinatal center in Berlin, Germany in 2014. Eighty-three women at term with a singleton pregnancy and cephalic presentation were included.

Results: In total, 60.2% of patients delivered vaginally, 4.8% by ventouse/forceps and 34.9% by secondary cesarean section. Parous women were found to have a significantly higher chance of vaginal birth (82.6% vs. 60.2% in total, p = 0.019). Patient’s ≥ 35 years showed a tendency towards increased rates of ventouse and cesarean section (11.1% vs. 4.8% and 38.9% vs. 34.9% respectively). There was a tendency towards a higher rate of vaginal birth in patients with previous cesarean section (66.7% vs. 59.2%). No adverse fetal or maternal outcomes were noted.

Conclusions: The application of Dilapan-S is cost-effective as patients can be seen in outpatient care. The device is efficient and safe. It is an attractive option for physicians and patients to lower the cesarean section rate by facilitating VBAC.

Introduction

Induction of labor grows in importance in the field of obstetrics as more and more pregnancies require inducement, particularly those associated with an unfavorable cervix[1]. Up to 50% of all labor inductions require cervical ripening, for which mechanical or chemical agents can be used[2].

Traditionally, mechanical devices such as the Foley catheter were widely used and later complemented by pharmacological methods. Recently there has been a revival of mechanical agents in clinical practice, likely due to the simplicity, safety and lower cost of these devices in comparison to chemical agents such as prostaglandins (PGE1, PGE2) and oxytocin. There is also a growing population of patients with prior cesarean section who desire a spontaneous vaginal delivery and often require induction of labor.

Various mechanical devices can be used to induce labor. The device is commonly inserted into the cervical canal or the extra-amniotic space and works through dilation of the cervical canal and/or the endogenous release of prostaglandins and oxytocin[3,4], the Foley urinary catheter being the most common device deployed. The balloon is then inflated and sometimes traction is applied. Due to the rapid and potentially painful expansion of the balloon, as well as the foreboding appearance of the device, the Foley catheter is not well-accepted by patients and physicians in the western world.

Other mechanical agents have been developed that overcome common prejudices against these devices. Some are hydrophilic agents made from sterile sea weed (known as laminaria tents) or synthetic materials (such as Dilapan-S or Dilasoft) that function through gradual radial expansion of the cervical canal as well as stimulating the release of endogenous prostaglandin and oxytocin[3,4]. To date, Dilapan-S has been described in literature as a useful tool in cervical preparation prior to dilation and evacuation in induced abortion < 20 gestational weeks[4,5].

Dilapan-S is a tiny rod made from synthetic hydrophilic material (Aquacryl 90) attached to a polypropylene handle. The device is inserted into the cervical canal and left overnight (12 hours) while it gradually dilates the cervix by absorbing local fluids and promotes the endogenous release of prostaglandins and oxytocin. The rod measures 4 by 55mm and dilates from 4 up to 8mm upon insertion into the cervical canal. Dilapan-S is available for daily clinical application in the labor ward. It is approved for the use in patients with previous cesarean section, in contrast to most of the available pharmacological agents. Importantly, patients are not necessarily admitted to the hospital when cervical ripening is performed. This makes the application of Dilapan-S an outpatient procedure and therefore a cost-effective alternative.

In this pilot study we evaluate the safety and efficacy of mechanical ripening of the cervix using Dilapan-S in a representative cohort of patients that presented in our tertiary perinatal center in Berlin, Germany with an indication for labor induction.

Methods

Study design and population

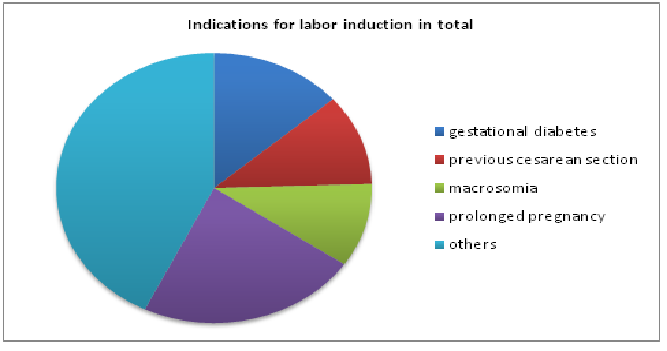

This is a descriptive observational study. 83 patients with term pregnancies (more than 36 gestational weeks) that had previously presented at our tertiary perinatal center in Berlin, Germany and were scheduled for labor induction. The Patients were pregnant with singletons that presented vertex. Upon application of Dilapan-S, membranes were intact and the cervix unfavorable (Bishop Score of less than 4). Maternal age, gravity and parity, pregnancy duration, cervical length at induction, Bishop Score throughout the procedure, mode of delivery (spontaneous, ventouse, cesarean) as well as maternal and fetal outcome were noted. The method of labor induction (Minprostin, Misoprostol, Prepidil, oxytocin, or nothing) following cervical ripening was recorded. Certain indications for inducement were assessed, such as gestational diabetes, diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, cesarean section in previous pregnancy, uterine operations, fertility treatment, IUGR (< 3.centile), abortion or miscarriage in previous pregnancy, macrosomia (> 90.centile), oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, prolonged pregnancy of more than 40 6/7 gestational weeks, suspicious CTG pattern, intrauterine death of fetus in previous pregnancy, obesity (Body Mass Index > 30) (Figure 1). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, Version 20.

Figure 1: Percentage of indications in total: gestational diabetes 13.6% (19.0%), previous cesarean section 10.9% (15.2%), macrosomia 10.0% (13.9%), prolonged pregnancy 22.7% (31.6%) and others 42.7% (59.7%). Percentage in cases is displayed in brackets, as in some cases more than one risk factor was mentioned. Other risk factors were: pre-excisting diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia/HELLP, other uterine operations, fertility treatment, IUGR, abortion/miscarriage, oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, suspicious CTG pattern, intrauterine fetal death in previous pregnancy, obesity, overweight.

Results

General findings

Cervical ripening prior to labor induction was performed in a group of 83 patients. The average age was 31 years. In this cohort, 60 out of 83 patients were nulliparae. 12 out of 83 patients had a cesarean section in a previous pregnancy. Mean pregnancy duration at day of cervical ripening was 40 gestational weeks. 23% of patients were at ≥ 40 6/7 gestational weeks. At cervical ripening, a mean cervical length of 24.5 mm and median Bishop Score of 2 was found. In total, 60.2% of patients delivered vaginally, 4.8% by ventouse/forceps and 34.9% by secondary cesarean section. Average time from cervical ripening to delivery was 1.5 days (36 hours). Most common indications for labor induction were prolonged pregnancy with 22.7% overall (31.6% in cases), gestational diabetes 13.6% (19.0%) and previous cesarean section 10.9% (15.2%) (Figure 1). In some subjects more than one indication was noted.

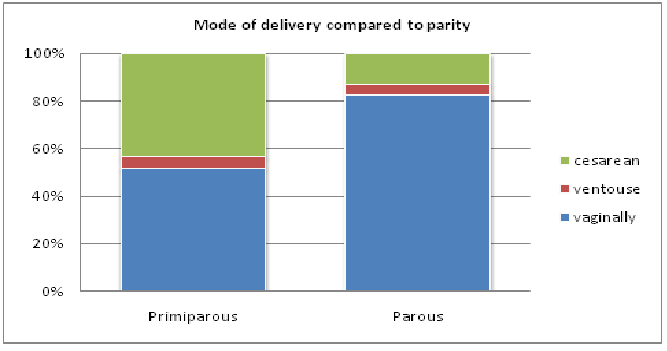

Parity

Multiparous women had a significantly higher chance of vaginal birth (82.6% vs. 60.2% in total, p = 0.019). 51.7% of nulli parous patients delivered vaginally(table 1), 5.0% via ventouse and 43.3% through cesarean section, compared to 82.6, 4.3 and 13% respectively in the group of multiparous women. It should be noted that 12 out of 23 patients in the multi Para group had a cesarean section in a previous pregnancy(Figure 2).

Table 1: Parity and mode of delivery, Fisher’s exact Test p = 0.019.

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Parity | Nulliparea | Number | 31 | 3 | 26 | 60 |

| % | 51.7% | 5.0% | 43.3% | 100% | ||

| ≥ one delivery | Number | 19 | 1 | 3 | 23 | |

| % | 82.6% | 4.3% | 13.0% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 29 | 83 | |

| % | 60.2% | 4.8% | 34.9% | 100% | ||

Figure 2: Parity and mode of delivery. Parous patients displayed a significantly higher rate of vaginal birth (82.6% vs. 60.2% in total, p = 0.019).

Maternal age

Average age of patients was 31 years. We grouped patients into two categories: < 35 years and ≥ 35 years. 18 out of 83 patients were 35 years and older at the time of cervical ripening and labor induction. In this group, a tendency towards decreased vaginal delivery was found (50.0% vs. 60.2% in total), with increased rates of ventouse and cesarean section noted (11.1% vs. 4.8% and 38.9% vs. 34.9% respectively)(Table 2).

Table 2: Maternal age compared to mode of delivery, Fisher’s exact Test p = 0.260

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Maternal age | < 35 years | Number | 41 | 2 | 22 | 65 |

| % | 63.1% | 3.1% | 33.8% | 100.0% | ||

| ≥ 35 years | Number | 9 | 2 | 7 | 18 | |

| % | 50.0% | 11.1% | 38.9% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 29 | 83 | |

| % | 60.2% | 4.8% | 34.9% | 100% | ||

Time to delivery

Average time from cervical ripening to delivery was 1.5 days (36 hours). 74.7% of patients gave birth within 48 h after cervical ripening was initiated (67.8% vaginally/instrumental vs. 32.2% cesarean section) (Table 3). A longer duration of cervical ripening and labor induction was associated with a significantly higher rate of delivery by ventouse or cesarean section (14.3% vs. 4.8% and 42.9% vs. 34.9% respectively).

Table 3: Time to delivery compared with mode of delivery, Fisher’s exact test p = 0.026

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Time to delivery | ≤48 hours | Number | 41 | 1 | 20 | 62 |

| % | 66.1% | 1.6% | 32.3% | 100% | ||

| >48hours | Number | 19 | 3 | 9 | 21 | |

| % | 42.9% | 14.3% | 42.9% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 29 | 83 | |

| % | 60.2% | 4.8% | 34.9% | 100% | ||

When analyzing prolonged pregnancies (≥ 40 6/7 gestational weeks), a trend towards an increased rate of secondary cesarean section (48.0% vs. 34.9% in total) was apparent. 52.0% of women in the prolonged pregnancy group delivered vaginally compared to 60.2% in total (Table 4).

Table 4: Prolonged pregnancy ( ≥ 40 6/7 gestational weeks), compared to mode of delivery, Fisher’s exact test p = 0.193.

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Prolonged pregnancy (≥40 6/7 gestational weeks) | No | Number | 37 | 4 | 17 | 58 |

| % | 63.8% | 6.9% | 29.3% | 100% | ||

| Yes | Number | 13 | 0 | 12 | 25 | |

| % | 52.0% | 0.0% | 48.0% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 29 | 83 | |

| % | 60.2% | 4.8% | 34.9% | 100% | ||

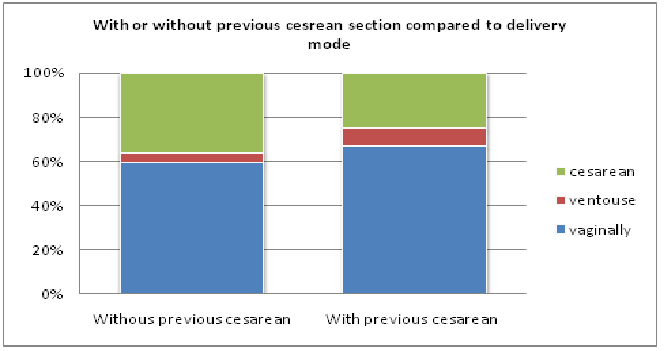

Cesarean section in previous pregnancy

In women requiring inducement with a history of cesarean section we observed a trend towards more vaginal birth compared to patients without previous cesarean section (66.7% vs. 59.2%). When including operative vaginal methods, 75.0% of patients with cesarean section in a previous pregnancy delivered vaginally, compared to 65.0% in total (Table 5).

Table 5: Mode of delivery compared to previous cesarean section, Fisher’s exact test p = 0.553.

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Cesarean section in previous pregnancy | No | Number | 42 | 3 | 26 | 71 |

| % | 59.2% | 4.2% | 36.6% | 100% | ||

| Yes | Number | 6 | 1 | 3 | 12 | |

| % | 66.7% | 8.3% | 25.0% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 29 | 83 | |

| % | 60.2% | 4.8% | 34.9% | 100% | ||

Induction after cervical ripening

The chosen method of labor inducement following cervical ripening was variable. 6 out of 82 patients (5.0%) required no further induction as they developed contractions(Figure 3). Five of this group delivered vaginally (including one ventouse delivery), while the other one delivered by cesarean section. 12 out of 82 patients (10.0%) displayed a Bishop Score of more than 5 and were subsequently induced with Oxytocin intravenously. 11 of these 12 patients gave birth vaginally. 64 out of 82 patients (53.1%) required further cervical ripening using either an application of Minprostin gel vaginally, Misoprostol orally, Prepidil gel intra cervically or a repeated application of Dilapan-S. These patients displayed a higher rate of cesarean section (40.5, 25.0, 44.4, and 42.9%, respectively) compared to the overall cesarean rate, to those who required no further induction, and to those given Oxytocin intravenously (34.9%, 16.7%, 8.3% respectively)(Table 6).

Figure 3: With or without uterine scar from a previous cesarean section compared to delivery mode.

Table 6: Mode of cervical ripening and or labor induction following Dilapan-S use in comparison to mode of delivery. Fisher’s exact Test p = 0.376.

| Mode of delivery | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaginally | ventouse | Cesarean | ||||

| Induction procedure following cervical ripening | None | Number | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| % | 66.7% | 16.7% | 16.7% | 100% | ||

| Minprostin gel vaginally | Number | 20 | 2 | 15 | 37 | |

| % | 54.1% | 5.4% | 40.5% | 100% | ||

| Misoprostol orally | Number | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| % | 75.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 100% | ||

| Prepidil gel intra cervically | Number | 5 | 0 | 4 | 9 | |

| % | 55.6% | 0.0% | 44.4% | 100% | ||

| Oxytocin intra venously | Number | 11 | 0 | 1 | 12 | |

| % | 91.7% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 100% | ||

| 2nd application of Dilapan-S | Number | 7 | 1 | 6 | 14 | |

| % | 50.0% | 7.1% | 42.9% | 100% | ||

| Total | Number | 50 | 4 | 28 | 82 | |

| % | 61.0% | 4.9% | 34.1% | 100% | ||

Maternal and fetal safety

Overall, one patient suffered from postoperative wound infection after cesarean section. In this instance the operation was performed due to failure to progress. There were no signs of amniotic infection syndrome and no fever at time of cervical ripening/labor induction in this case. One patient that delivered vaginally suffered from a perineal tear, grade ≥ III. No other complications, such as uterine hyper stimulation and/or excessive bleeding ≥ 1000ml, were found.

Discussion

Induction of labor is the iatrogenic provocation of uterine contractions that is intended to trigger spontaneous labor and ultimately result in vaginal delivery. Rates of induction of labor are increasing. In 2013 23% of all pregnant women in the United States underwent induction of labor compared to 9.5% in 1990[7]. It is often a time-consuming process, as the period from cervical ripening and/or induction until the entrance to the labor ward with subsequent delivery can range from hours to days, and maintaining patient motivation to continue the process of labor induction may be unpredictably challenging. The question arises: what to do when induction fails? In the United States, 10% of all non-successful inductions result in a cesarean section[8]. Numerous investigations and clinical trials are conducted in this field in order to analyze fetal and maternal safety in cases of cervical ripening and induction of labor.

Here we present our first experiences in daily clinical use with the hydrophilic device Dilapan-S in a small but representative group of patients with term pregnancies. The device is inserted intracervically by a physician in our prenatal consultation clinic. Following the procedure, a CTG is recorded and the patient can be discharged. Dilapan-S is left in overnight (at least 12 hours) and the patient presents herself in the clinic the next morning. In this study only one Dilapan-S was inserted for the first round of cervical ripening. In the future we will assess the impact of multiple inserted osmotic dilators on the time required from cervical ripening to delivery.

The application of Dilapan-S is an outpatient procedure and therefore allows to avoid the costs of patient admission (as is required for the use of Prostaglandins or Oxytocin)[9]. Only patients with certain risk factors, such as previous cesarean section, were admitted to the hospital for further monitoring. Average time from cervical ripening to delivery was 36 hours.

Parity and age

We found that parous women displayed a higher rate of vaginal birth compared to nulli parous patients. This finding conforms with the literature, as being nulli parous was identified as a contributor to the likelihood of a cesarean section[10,11]. In the present study, we established that women older than 35 years were more likely to have a cesarean section, which corresponds to results from recent research. Gareen et al revealed that the cesarean section rate is higher in patients > 35 years compared to those < 35 years (after adjustment, in nulli parous women)[12].

Time interval to delivery

Minimizing the interval to vaginal delivery is a key objective in every obstetric hospital with respect to labor induction[11]. When using the osmotic dilator, patients are seen as outpatients and can enjoy some time at home in a “safe environment” before the onset of labor. When applying pharmacological agents, by contrast, admittance to the labor ward is obligatory. Median time to delivery depends on the medical agent used and ranges in the literature from 21-32 hours (e.g. 200 μg Misoprostol vaginally, 10 mg dinoproston vaginally)[13]. In our study the median time to delivery was 36 hours. However, when subtracting the fact that the osmotic dilator was used as an ambulant procedure, only duration of 12 hours was spent in the hospital, saving at least one night of hospital admission. There are some additional delays in the labor ward itself, while the Dilapan-S device was extracted and induction adjourned depending on the treating midwife/physician, time of day and wish of patient. Further assessment of the time intervals has to be done in larger cohorts.

Prolonged pregnancies

Prolonged and post-term pregnancies are associated with increased maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality and are considered a risk condition and require special monitoring[14,15,16]. These pregnancies are often the subject of induction of labor. Studies analyzing labor induction at 41 weeks and more suggested lowered rates of cesarean section and stable or reduced perinatal morbidities[15,17]. Other studies indicate increased cesarean rates in nulli parous women and stable perinatal and maternal morbidity[18]. We observed a trend of increased cesarean section rate in pregnancies of ≥ 40 6/7 gestational weeks. This might be due to multiple reasons, like other pregnancy-associated risks and the wishes of the patient and her family. Notably, labor induction alone is attributed with an increased chance of cesarean section[19]. Further research in this field must be done to compare pregnancies of ≥ 41 0/7 gestational weeks with and without risk factors when studying labor induction.

VBAC

A rising number of patients have previously delivered via cesarean section. Many of these women achieve a vaginal birth (vaginal birth after cesarean section = VBAC) and sometimes require cervical ripening and subsequent labor induction. The usually prescribed pharmacological agents (Prostaglandins, Oxytocin) are not licensed for the use in this particular group of patients, meaning many women had to have an elective repeat cesarean section (ERCS) if they did not present with spontaneous labor in the past. This is how our interest in the use of Dilapan-S first arose, as this product is licensed in women with a previous cesarean and consequently offers an alternative route for these patients and their treating physicians. The chance of VBAC is a viable option for increasing the overall rate of vaginal deliveries[20].

Success rate of VBAC is described in literature to be between 60- 80%[21]. In this current study we found that the group of patients who seek VBAC displayed a slightly higher rate of vaginal birth (75.0% vs. 65.0% in total, including ventouse). This might be due to the “non-medical” fact that these patients were highly motivated to delivery vaginally and undertook measures to increase this likelihood, such as avoiding weight gain in the current pregnancy and exercising more. More important probably is the fact that these patients were predicted as very likely to give birth vaginally by their treating physician. Other women with previous cesarean section that were not predicted to deliver vaginally were more likely scheduled for an ERCS.

In the future, a randomized controlled study would be necessary to rule out this bias (e.g. expectant management vs. Dilapan-S induction at 41 0/7 gestational weeks). Furthermore, some prediction models are available on the success rate of VBAC that can be utilized in this process[20,22].

Comparison to pharmacological agents: In the Cochrane review on mechanical induction of labor from 2012, no discrepancy in cesarean section rates was found when comparing mechanical with pharmacological agents[4]. Interestingly, mechanical methods of labor induction were associated with a lower chance of achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours. Nonetheless, mechanical methods compared to prostaglandins were found to have a decreased chance of hyper stimulation and fetal heart rate modulation[4,23]. In a review from 2011 mechanical agents were found to be more successful in women with an unfavorable cervix compared to the usage of Oxytocin alone[24,25].

Critical Assessment of this study and future outlook: We have presented our first clinical experiences with Dilapan-S in an observational setting with a small group of patients. The results agree with findings from literature when analyzing other mechanical agents. Further multi-center studies with a randomized, controlled approach should be conducted to compare osmotic dilators with pharmacological agents. The patient’s satisfaction concerning the ripening and induction method should be assessed in a standardized manner, as this is an important factor in daily clinical work.

Conclusion

In this study we analyzed cervical ripening with a promising mechanical device that is comparable to pharmacological methods. It can be used in an outpatient procedure, thereby reducing costs by minimizing hospital admissions. The osmotic dilator is easy to apply and can be effortlessly inserted by a physician or midwife. Our patients had no complaints whatsoever, neither during insertion, dilation nor extraction of Dilapan-S. Such a device also presents a possibility for labor induction in women with previous cesarean section for whom pharmacological means are not licensed. In the future we will continue this work within a randomized controlled setting to compare with other methods of labor induction.

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1. Brennan, D.J., Murphy, M., Robson, M.S., et al. The singleton, cephalic, nulliparous woman after 36 weeks of gestation: contribution to overall cesarean delivery rates. (2011) Obstet Gynecol 117: 273-279.

- 2. Stephenson, M.L., Wing, D.A. A novel misoprostol delivery system for induction of labour: clinical utility and patient considerations. (2015) Drug Des Devel Ther 22(9): 2321-2327.

- 3. Drunecky, T., Reidingerova, M., Plisova, M., et al. Experimental comparison of properties of natural and synthetic osmotic dilator. (2015) Arch Gynecol Obstet 292(2): 349-354.

- 4. Fox, M.C., Krajewski, C.M. Cervical preparation for second-trimester surgical abortion prior to 20 weeks’ gestation: SFP Guideline #2013-4. (2014) Contraception 89(2): 75-84.

- 5. Lyus, R., Lohr, P.A., Taylor, J., et al. Outcomes with same-day cervical preparation with Dilapan-S osmotic dilators and vaginal misoprostol before dilation and evacuation at 18 to 21+6 weeks’ gestation. (2013) Contraception 87(1): 71-75.

- 6. Jozwiak, M., Bloemenkamp, K.W., Kelly, A.J. et al. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. (2012) Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- 7. Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Osterman, M.J., e al. Birth: final data for 2013. (2015) Natl Vital Stat Rep 64(1): 1-65

- 8. Spong, C.Y., Berghella, V., Wenstrom, K.D., et al. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists workshop. In reply. (2013) Obstet Gynecol 121(3): 687.

- 9. Sciscione, A.C. Methods of cervical ripening and labor induction: mechanical. (2014) Clin Obstet Gynecol 57(2): 369-376.

- 10. Trifuno, S., Ferrazzani, S., Lanzone, A., et al. Identification of obstetric targets for reducing cesarean section rate using the Robson Ten Group Classifictation in a tertiary level hospital. (2015) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 189: 91-95.

- 11. Robson, M.S. Can we reduce the caesarean section rate? (2001) Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 15: 179-194

- 12. Gareen, I.F., Morgenstern, H., Greenland, S., et al. Explaining the association of maternal age with Cesarean delivery for nulliparous and parous women. (2003) J Clin Epidemiol 56: 1100-1110.

- 13. Wing, D.A., Brown, R., Plante, L.A., et al. Misoprostol vaginal insert and time to vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. (2013) Obstet Gynecol 122: 201-209.

- 14. Lundgren, I., Smith, V., Nilsson, C., et al. Clinician-centered interventions to increase vaginal birth after cesarean section (VBAC): a systematic review. ( 2015) BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

- 15. Fagerberg, M.C., Marsal, K., Källen, K. Predicting the chance of vaginale delivery after one cesarean section. validation and elaboration of a published prediction model. (2015) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 188: 88-94.

- 16. Gülmezoglu, A.M., Crowther, C.A., Middleton, P., et al. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. (2012) Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- 17. Annessi, E., Del, Giovane, C., Magnani, L., et al. A modified prediction model for VBAC, in a European population. (2015) J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 14: 1-5.

- 18. Birara, M., Gebrehiwot, Y. Factors associated with success of vaginal birth after one caesarean section (VBAC) at three teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a case control study. (2013) BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

- 19. Mozurkewich, E.L., Chilimigras, J.L., Berman, D.R., J, et al. Methods of induction of labour: a systematic review. (2011) BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

- 20. Heimstad, R., Romundstad, P.R., Salvesen, K.A. Induction of labour for post-term pregnancy and risk estimates for intrauterine and perinatal death. (2008) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87: 247-249.

- 21. Sanchez-Ramos, L., Olivier, F., Delke, I., et al. Labor induction versus expectant management for postterm pregnancies: a systematic review with meta-analysis. (2003) Obstet Gynecol 101: 1312-1318.

- 22. Kruit, H., Heikinheimo, O., Ulander, V.M., et al. Management of prolonged pregnancy by induction with a Foley catheter. (2015 ) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94(6): 608-614.

- 23. Little, S.E., Caughey, A.B. Induction of Labor and Cesarean: What is the True Relationship? ( 2015) Clin Obstet Gynecol. 58: 269-281.

- 24. Wing, D.A., Sheibani, L. Pharmacotherapy options for labor induction. (2015) Expert Opin Pharmacother 16(11): 1657-1668

- 25. Thomas, J., Fairclough, A., Kavanagh, J., et al. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. (2014) Cochrane Databas Syst Rev.