Dynamics of Cattle Price Determination in Mubi International Livestock Market, North-Eastern, Nigeria

Affiliation

Department of Animal Production and Health, Federal Polytechnic, Nigeria

Corresponding Author

Kubkomawa Hayatu Ibrahim, Department of Animal Production and Health, Federal Polytechnic, Pmb 35, Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria, Tel: +2347066996221; E-mail: kubkomawa@yahoo.com

Citation

Kubkomawa, H.I. Dynamics of Cattle Price Determination in Mubi International Livestock Market, North-Eastern, Nigeria. (2017) J Vet Sci Animal Welf 2(1): 1- 12.

Copy rights

© 2017 Kubkomawa, H.I. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Dynamics; Price determination; Cattle; Market; North-East; Nigeria

Abstract

The objectives of the study were to examine the dynamics of price determination and major constraints faced by cattle marketers in Mubi international livestock market, Adamawa State, Nigeria. One hundred (100) marketers were randomly selected for interviews and discussion on cattle marketing dynamics. Data generated were subjected to descriptive statistics to explain the trend of cattle marketing in the study area. Market prices of cattle in Mubi are determined by visual evaluation which incorporates element of indicators such as breed, age, sex, colour, body condition score, temperament, anus stain and the purpose of buying the animals. Inadequate market information, manipulative ways of market intermediaries, high cost of transportation, lack of infrastructure and credit facilities, fluctuation in demand and supply, cattle rustling and buying of stolen animals, inadequate security within the market place and on the roads and payment of heavy taxes and clearing of checkpoints on the roads formed constraints faced by the marketers. Therefore, a cattle marketing in the study area and Nigeria, in general, is predominantly controlled by intermediaries who benefit more, while primary producers and the end consumers do not get the desired value for their efforts. It is recommended that, since cattle marketing are not isolated from national and international political and socio-economic policies, the interactions between the marketers and broader sectors should be taken into account in order to generate holistic and reliable data that would inform effective interventions.

Introduction

Nigeria is one of the leading countries in cattle production in sub-Saharan Africa[1]. In 2008, the country had over 14.73 million cattle consisting of 1.47 million milking cows and 13.26 million beef cattle. Less than 1% of this population is managed commercially while the remaining ones are managed traditionally[2]. Under this system, there is the use of indigenous methods in all aspects of cattle production including marketing and health management[3,4]. This tilt towards the traditional management will have grave implications on cattle production, commercialization of cattle products and price determination. Cattle singly contribute about 12.7% of the agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) in Nigeria[5]. The cattle industry provides a means of livelihood for a significant proportion of the livestock rearing (pastoral) households and participants in the cattle value chain in the sub-humid and semi-arid ecological zones of Nigeria[6,7,8]. Although, there are many sources of animal protein in Nigeria, recent studies have shown that, cattle products are the predominant and the most commonly consumed animal protein sources. Thus, cattle are a highly valued livestock in Nigeria[1,2,9] where they are kept for beef, hide, milk or for traction[1,10]. To some producers, cattle serve as a status symbol[2]. From the foregoing, it is obvious why cattle production and marketing are notable employment and income-generating livelihood activities for many Nigerians[11].

Cattle and beef trade provides the largest market in Nigeria with millions of Nigerians making their livelihood from various beef-related enterprises[12]. Consequently, the outcome of enhanced production and marketing of cattle and its products carry the potentials to better the income and nutritional status of households and positively impinge on their living standards. Efficient marketing plays an important requirement in the attempt to achieve wider accessibility and affordability of any product to consumers[13]. This is obvious from the long established adage that, production and marketing constitute a band. Thus, lack of development in one will necessarily obstruct development in the other[14-16].

Marketing encompasses all business activities associated with the transfer of a product from the producers to the consumers[17]. In the case of cattle, it is concerned with the movement of cattle from the pastoralists in the production locations in Northern Nigeria to the final consumers who are usually resident in Southern Nigeria[18]. The cattle marketing process makes possible the delivery of cattle to the buyers in the form, place and time needed. This process of bringing the cattle from where they are surplus or produced to where there are shortages or are consumed, a process known as arbitraging, needs to be fully understood to enhance the efficient working of cattle markets, which is vitally important in achieving sustainable and profitable agricultural commercialization in the livestock sub-sector in Nigeria[13,19]. Marketing is an economic activity which stimulates further production and if efficiently done, both the producer and consumer get satisfied in the sense that, the former gets a sufficiently remunerative price for the product to continue to produce while the latter gets it at an affordable price that stimulates continued consumption[19,20].

According to the National Livestock Project Division[21], the supply of cattle and its products has witnessed a decline while the demand has been increasing with the result being a shortfall in the supply. The high cost of marketing cattle is often the commonly cited culprit for this situation. Owing to the considerable spatial separation of production area from consumption area and other ancillary factors, there is high handling cost especially in relation to cattle transportation[22]. The broad objective of the study is to examine the dynamics of cattle price determination in Mubi international livestock market, Adamawa State, Nigeria. The specific objectives are to: Examine the socio-cultural characteristics of intermediaries and stakeholders in Mubi cattle market; Identify the cattle marketing channel and conduct of cattle marketers; Identify the factors that influence cattle price determination; Identify the major constraints faced by the cattle marketers.

Materials and Methods

The study area

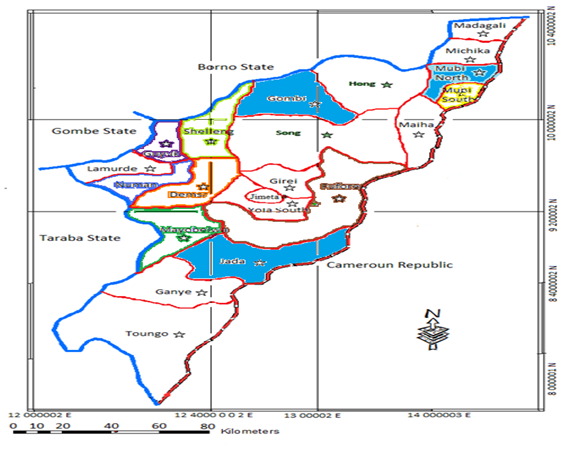

Adamawa State is located at the area where the River Benue enters Nigeria from Cameroon Republic and is one of the six states in the North-East geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It lies between latitudes 7° and 11° North of the Equator and between longitudes 11° and 14° East of the Greenwich Meridian[23]. It shares an international boundary with the Republic of Cameroon to the East and interstate boundaries with Borno to the North, Gombe to the North-West and Taraba to the South- West[24,25], as shown in (Figures 1a).

Figure 1: The Map of Nigeria Showing Adamawa State.

According to[26], Adamawa State covers an area land mass of about 38,741 km². The state is divided into three Senatorial Zones (Northern, Central and Southern) which translated to agricultural zones as defined by[27], which are further sub-divided into 21 Local Government Areas (LGAs) for administrative convenience. The State has a population of 2,102,053 persons[28]. The main ethnic groups in the state are the Kilba, Higgi, Quadoquado, Lala, Yungur, Bwatiye, Chamba, Mbula, Margi, Ga’anda, Longuda, Kanakuru, Bille, Bura, Yandang, Fali, Gude, Verre, Fulani and Libo[24,26,29]. The dominant religions are Christianity and Islam, although some of its inhabitants still practice traditional African religions. The major occupation of Adamawa people is farming. The soil type is ferruginous tropical soils of Nigeria based on genetic classification of soils by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations[30]. The soils are a function of the underlying rocks, the seasonality of rainfall and the nature of the wood-land vegetation of the zone. The soils are derived from the basement complex, granite and gnesis that form the ranges of mountains. The mineral resources found in the state include iron, lead, zinc and limestone[26].

The common relief features in the state are the Rivers Benue, Gongola, Yadzaram and Kiri Dam, Adamawa and Mandara mountains and Koma hills. The state has minimum and maximum rainfalls of 750 and 1050 mm per annum and an average minimum and maximum temperature of 15°C and 32°C, respectively. The relative humidity ranges between 20 and 30% with four distinct seasons that include early dry season (EDS, October – December); late dry season (LDS, January – March); early rainy season, (ERS, April – June) and late rainy season (LRS, July – September), according to[24]. The vegetation type is best referred to as guinea savannah[26,31]. The vegetation is made up of mainly grasses, aquatic weeds along river valleys and dry land weeds inter-spersed by shrubs and woody plants. Plant heights ranges from few centimeters (Short grasses) to about one meter tall (tall grasses), which form the bulk of animal feeds. Cash crops grown in the state include cotton and groundnuts, sugarcane, cowpea, benniseed, bambara nuts, tiger nuts, while food crops include maize, yam, cassava, sweet potatoes, guinea corn, millet and rice. The communities living on the banks of rivers engage in fishing, while the Fulani and other tribes who are not resident close to rivers are pastoralists who rear livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, few camels, horses and poultry for subsistence[24,26].

The study site Mubi South LGA is located at the Northern part of old Sardauna Province, which now forms Adamawa North Senatorial district as defined by[27] as shown in (Figure 1b). The region lies between latitude 9° 30´´ and 11° North of the Equator and longitude 13° and 13° 45´´ East of Green witch Meridian. It has an altitude of 696 meters above sea level with an annual mean rainfall of 1,220 mm and a mean temperature of 15.2°C during Hamattan periods from November to February and 39.7°C in April[32]. The town essentially has a mountainous landscape transverse by River Yedzaram and many tributaries. Mandara and Adamawa Mountains form part of this undulating Landscape[33]. The Gude, Fali, Fulani and other tribes dominate the area which has a lot of pasture land. Mubi region is bordered in the North by Borno State, in the West by Hong and Song LGAs and in the South and East by the Republic of Cameroon. It has a land area of about 4,728.77 km² and human population of about 759,045, going by[28] NPC, (1991) census projected figure[34]. It has an international cattle market linking neighboring and other countries such as Cameroon, Chad, Central Africa, Niger, Mali and Senegal to Southern Nigeria where cattle are consumed.

Figure 1b: The Map of Adamawa State Showing the Study Areas in Yellow Color.

Selection of respondents and sampling design

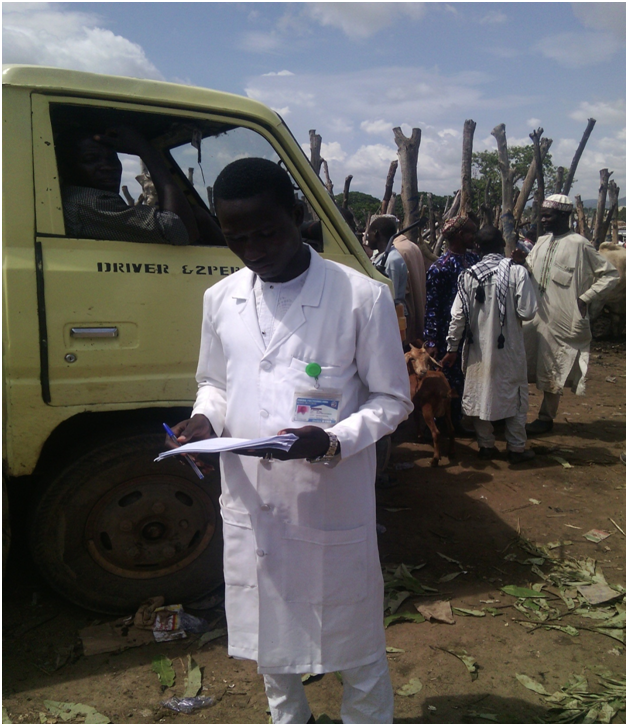

The research covered a period of four weeks, during the survey, visits were paid to Mubi international livestock market and respondents identified. The objective of the study was explained to them and their permission obtained to participate in the study as shown in (Figure 2). Actual participation in the study was based on the willingness of respondents.

Data collection

Twenty five (25) marketers were randomly selected on each of the market days for oral interviews, discussion and physical observations on marketing of cattle as can be seen in (Figure 2). Overall, 100 marketers were engaged for interviews, direct observations and data collection. This was done across four market days (every Tuesday) in July, 2016. The structured questionnaire were developed in English language and used to collect information on cattle market structure, socio-cultural characteristics of intermediaries and all the stakeholders, price determination dynamics, production areas, transportation methods and stakeholders satisfaction. Where a farmer did not understand English, vernacular languages were used.

Figure 2: Researcher Interviewing and Discussing with Cattle Marketers.

Data analysis

Data generated from the survey were subjected to descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentages and means to explain the trend of marketing in the study area.

Results and Discussion

Socio- cultural characteristics of cattle marketers in mubi south L.G.A

(Table 1) highlights the socio-cultural characteristics of cattle marketers in Mubi South L.G.A., Adamawa State, Nigeria.

Table 1: Socio - Cultural Characteristics of Cattle Marketers in Mubi South L.G.A.

| Parameter | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Age distribution (in years) | ||

| 20 - 50 | 75 | 75 |

| 51- above | 25 | 25 |

| (b) Sex distribution | ||

| Male | 95 | 95 |

| Female | 5 | 5 |

| (c) Marital status | ||

| Married | 85 | 85 |

| Single | 10 | 10 |

| Divorced | 5 | 5 |

| (d) Qualifications | ||

| W/Education | 10 | 10 |

| Nomadic/Arabic | 90 | 90 |

| (e) Market experience | ||

| 5 - 15 | 85 | 85 |

| 16 – above | 15 | 15 |

| (f) Tribal distribution | ||

| Hausa/Fulani | 95 | 95 |

| Others | 5 | 5 |

| (g) Religious affiliations | ||

| Islam | 85 | 85 |

| Christianity | 10 | 10 |

| Traditional | 5 | 5 |

Age distribution of cattle marketers: (Table 1a) presents the results of cattle marketers based on age group which indicates that, seventy five percent (75%) are between the ages of 20 and 50 years, while twenty five percent (25%) fall within the age group of 51 years and above. This implies that, youths are more engaged in the business of buying and selling of cattle in the study area. This is, also, possible because of the hectic and tasking nature of the business which requires enough strength characterized by a lot of brain work from the price negotiation to chasing, restraining, loading, off-loading and even transportation of the animals via hoof or vehicle to the end consumers as shown in (Figures 3,4,5,6 and 7).

However, the aged (51 years old and above) can also, successfully participate in cattle marketing business to earn a legitimate living with a little assistance from the young people. The results of this study agree with the report of[30] which stated that, younger people are more actively involved in the cattle business in Africa.

The results, also, corroborated that of[35], who reported similar findings of 41 to 50 years old as major ages of cattle marketers in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. This means that, majority of the cattle marketers in Nigeria are still young and are within the active working class. This is, however, expected to influence their productivity and efficiency in the rigorous and energy sapping cattle marketing business.

Figure 3: Cattle Marketers Off-loading Animals from a Vehicle.

Figure 4: Marketers in Group Doing Transaction and Negotiating Prices.

Figure 5: Another Group of Marketers Doing transaction and Negotiating Prices.

Figure 6: Marketers Loading Purchased Animals for Shipment to the South.

Figure 7: A Truck Fully Loaded from Mubi and Off to Southern Nigeria.

Sex distribution of cattle marketers: (Table 1b) revealed that, about ninety five percent (95%) of cattle marketers in the study area are male, while only five percent (5%) are female. This was, also, possible because cattle marketing business in Africa and Nigeria in particular involves physical activities like struggling and wrestling to control the cattle using sticks and robes. The business is full of risk and hazards as some animals are wild and dangerous. The animals can fight their way to escape being sold and taken away. In addition, the Northern muslims, which form the largest population of the marketers, do not allow their wives to go out for such hard business, as reported by[36] and[37]. It was additionally observed that, all cattle marketers had to watch their backs in case of attack as they walk and meander amongst the animals tethered to begs, with others roaming about freely. It was also gathered that, people have been killed in the past by some sharp-pointed horned wild and temperamental animals. Apart from the risk of been hurt by the animals, there is also fear of armed robbers striking the market at any time since no security agents are physically seen around to scare armed robbers away. Some marketers use charms to enable them maneuver their ways easily within the market without any challenge from the animals. Others use charms to make animals docile and easy to handle, to make sellers to sell at a giveaway price and for protection against theft and intimidation from rivals. To ensure that the cattle business thrives and grow in capacity, cattle marketing business is usually ritualized. Marketers also confirmed that, during the dry season the market used to be over-crowded with a lot of people coming to buy cattle for either festivities or for shipment to the south. The entire market would be dusty, noisy and smoky. During the rainy seasons, the market is also dirty with waters mixed with cattle feces and left over feeds forcing marketers to use rain boots and coats, as shown in (Figures 3,4,5,6).

Generally, men have the highest percentage of cattle business holdings because they are the bread winners, having reservoir of wealth and taking the responsibility of managing herds to sustain the family’s livelihood. However, women and children, although relegated to the background, also control portions of the livestock holdings to support the family[38]. Iro (1994) reported that, cattle belong to individual family members and are usually managed and sold together with male family members assuming automatic rights to all cattle, making it difficult to determine cattle ownership by female family members[39] Swinton however, reported that, women own most of the small ruminants and almost all of the poultry flocks.

Marital status of cattle marketers: (Table 1c) shows that, eighty five percent (85%) of the cattle marketers in the study area are married, ten percent (10%) single, while five percent (5%) divorced. This shows that, majority of the cattle marketers are responsible Nigerians doing their lawful business to earn a living and support families. It also implies that, cattle marketing business is a profitable venture and if regulated well by the agencies concerned in the study area and Nigeria as a whole, it could keep on sustaining enumerable individuals and families. The results are in agreement with similar findings obtained by[40] Kohls and Uhls.

Educational qualifications of cattle marketers: (Table 1d) presents the educational qualifications of cattle marketers in the study area. The results indicates that, ninety percent (90%) had Nomadic/Arabic education, while only ten percent 10%) had Western education. This implies that, majority of the marketers lack formal education because of their tribal and religion affiliations which do not encourage Western education. Again, this low level of Western education recorded amongst the cattle marketers in this study may be connected to their family backgrounds who were born and brought up in the rural areas and have herded before coming to settle in the city. This lack of Western education is a great set back to them and will have negative impact in the business of cattle marketing in the study area. The results coincide with that of[41] Mubi et al. (2012) who reported similar findings in Mubi South L.G.A., Adamawa State Nigeria. However, the results are in contrast with[42] Wakili (1996), who reported more cattle marketers with Western education than those with Qur’anic education in Gombe State, Nigeria.

Marketing experience of cattle marketers: (Table 1c) shows that, all the marketers had enough experiences in the business with eighty five percent (85%) having 5 - 15 years, while fifteen percent (15%) had 16 years and above. This also implies that, many of the marketers have been in the business for a long period of time and it is a true reflection of their ages as majorities are youths. It was observed that, Mubi South cattle market is fast expanding with high number of cattle trooping in and more people joining the business. The results corroborated that of Mubi, et al.[41], who reported similar findings in Mubi South L.G.A., Adamawa State Nigeria.

Tribal Distribution of Cattle Marketers: The results show that, ninety five percent (95%) of cattle marketers in the study area are from Hausa/Fulani tribes, while only five percent (5%) formed the other tribes, as shown in (Table 1f). This is because in the time past, people from other tribes considered cattle marketing as a lazy man’s business and that it is only relevant to those who herd and produce cattle. It was also observed that, Hausa-Fulani men always try to block other tribes from knowing the secret and joining the business. Any person who is not from Hausa-Fulani tribe, even with some certain percentage of cattle holdings, will have to come to the market through Hausa-Fulani middleman to sell his animals on commission. That is how Hausa- Fulani men earn their living year-in-year out at the expense of other tribes without investing anything. They hate to see the market saturated with other tribes since that will affect their income. They come to the market with empty pockets and get home with about ten (N10,000) to twenty (N20,000) thousand naira per market day, even after doing some shopping.

The few cattle marketers recorded by other tribes in this study are those category of people who don’t have alternative business, otherwise they would have opted for other businesses. Most of them serve under their masters as apprentices with little or no capital of their own. Those masters are usually from the Hausa-Fulani tribe. The apprentices are recruited perhaps just to strike a balance in the market ethnicity ratio and not to grow and become dealers or retailers like the Hausa-Fulanis. Other reason for recruiting such apprentices is to help in case other tribes come to sell their animals, the non-Hausa-Fulani apprentices will flow better in such transactions.

Religious affiliations: The results as shown in (Table 1g) depict that, eighty five percent (85%) of the cattle marketers are muslims, while ten (10%) and five percent (5%) are christians and traditionalist, respectively. This is quite possible because of their tribal status which indicated that, most of them are Hausa-Fulani by tribe and are well known for Islamic religion. This is evident that, when it is time for the normal 5-time prayers, the entire market remains quiet and stand still. The few non-muslims would be sighted in groups here and there, waiting. They are the people always acting at the background unable to take decisions of their own for fear of intimidation and if they do not dance to the tune of their Hausa-Fulani masters, they would be frustrated out of the business in no time.

Marketing dynamics

Marketing agents: The results in (Table 2) show that, the marketing dynamics among other things in Mubi South L.G.A include ten percent (10%) Brokers/Middle men (Barandas), fifteen percent (15%) Retailers, twenty five percent (25%) Dealers/Wholesalers (Dillalai), ten percent (10%) Butchers and fourty percent (40%) Producers (crop farmers, fatteners, pastoralists and institutions). The Brokers or Middle men, commonly known as Barandas, are like market thugs who hang around the sheds in various markets in Nigeria purportedly waiting to provide help or assistance to new buyers or sellers usually regarded as amateurs in the cattle business. The new buyers are majorly final consumers (group of individuals, householders, restaurant operators, cooperative members etc) or sub-retailers who come to buy cattle from dealers or retailers in small numbers for re-sale to prospective buyers or farmers who come to sell and buy replacement stocks or those who fatten cattle at homes. It is, usually, more costly to buy through the brokers, because they charge high commissions. Thus, experienced cattle buyers avoid doing business with them. These accounts for the reason brokers concentrate their attention on new buyers or sellers who are novices or beginners in the cattle business. These results agree with[35,43], who reported similar findings in South-Western Nigeria.

Table 2: Market Structure, Production, Transportation Systems and Source of Capital.

| a | Agent | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brokers / Middle men (Barandas) | 10 | 10 | |

| Retailers | 15 | 15 | |

| Dealers/ Wholesalers (Dillalai) | 25 | 25 | |

| Butchers | 10 | 10 | |

| Producers (crop farmers, those who do home fattening, pastoralists and institutions) | 40 | 40 | |

| b | Membership of market association | 50 | 50 |

| c | Production system | ||

| Pastoral | 75 | 75 | |

| Institutions | 10 | 10 | |

| Home fattening | 15 | 15 | |

| d | Transportation system | ||

| Hoof | 40 | 40 | |

| Vehicle | 60 | 60 | |

| e | Source of capital | ||

| Personal savings | 45 | 45 | |

| Friends and relations | 15 | 15 | |

| Bank | 25 | 25 | |

| Cooperatives | 15 | 15 |

Retailers, as the name implies, are traders in the cattle market and majority of them buy cattle from the cattle dealers or directly from the producers or sellers. Retailers may have animals between 5-10 in their stock at any given point in time. It was observed that, majority of them are formerly cattle dealers who, owing to aging, can no longer afford the stress and risk of travelling long distances to other markets to source for cattle. Also, few of them are retirees, who have reasonable capital from their retirement benefits, thus, affording them the capital required to operate at this level of cattle marketing. The ages of retailers ranged from 51 years and above who are also, responsible for distributing animals to butchers, local traders and directly to final consumers who need between one to five animals for restaurant business or for social gatherings and ceremonies. These results again support[35], who reported similar findings in South-Western Nigeria.

Dealers or Wholesalers, popularly known as Dillalai, in the cattle market in the study area and elsewhere in Nigeria, are marketers who source well fed animals, mostly males from different local markets within and outside the state and fatten them, then assemble and transport them to Mubi international cattle market for shipment down south. They are mostly young and active men between the ages of 20 and 50 years old. They command a lot of respect and are very influential in the cattle market setting because of the considerable amount of capital that is required to operate at this level. Some of them source their capital from financial institutions like commercial banks, relations, friends, cooperatives and the government. They are well travelled and known to pastoralists, crop producers who buy cattle for draft, institutions, people who do home fattening, local assemblymen and transporters in the Northern states of Nigeria and other neighbouring countries like Chad, Cameroon, Central Africa, Niger, Mali and Senegal. Sometimes, they operate through agents who represent and act on their behalf in other states or countries while they are in one state or country arranging for cattle purchase and transportation. Dealers are known to buy and transport between 50 and 200 cattle at each trip to the terminal markets. They make about 10 trips per year at an average of one trip per month. In all the cattle markets, it is one of these dealers that is usually elected chairman of the cattle market association. The results also buttressed similar findings reported by[35] in South-Western Nigeria.

Butchers are persons who buy animals, slaughter, dress, sell the meat or do any combination of these three tasks. They come to the market purposely to scout for old culled cheap animals (gambaye) for slaughter at the abattoir and distribute to various meat selling points within the city or transport it to nearby markets. They also, go for sick animals which cannot be bought by farmers for grazing no purchased by cattle dealers who ship animals to the Southern Nigeria. The butchers negotiate prices very well and make sure the cost of buying the animals favors them at the expense of the producers. These Butchers normally don’t have enough money for the business. Most times, they buy on credit or pay in installments or try to beat down cost by all means. They hardly go for healthy or well fattened animals and normally buy only few animals, like 2 - 3, at a time. Other category of marketing agents include: Crop farmers and pastoralists who perhaps come to the market to sell old culled or fattened animals or grains to get young animals as a replacement stock. Sometimes, they sell the animals to get money for salt lick, potash, drugs, bride price, settling court case, etc. Many at times they are cheated by selling their animals at a give-away price depending on the magnitude of the problem or reason for selling. These agents buy heifers, bullocks and young cows with one or two parity. They pay any amount suitable to them as measured by the desirable characteristics or traits possessed by the animals. they usually go for 2 - 4 animals at a time and are chased home in hoof or transported in pick-up vehicles.

There are other groups also, who do home fattening or fatten at the market square using concentrates such as brands, hay, cowpea husks, groundnut hum and cotton seed cake meals. The types of animals brought by them look healthy, sound with good body conformation scores. The animals attract higher prices, especially when there are many dealers with few animals to buy. These people buy their fattening stock during the dry season when the animals have lost a lot of weight because of lack of enough pasture and poor nutrient content of the forages. They fatten the animals for three to four months and bring them out for sale.

The last category of market agents are the institutions, who cull their animals in mass and are brought to the market to source for replacement stock, buy drugs, feeds, salt lick and for administrative purposes. This group hardly sells in singles, mostly if their animals are not slaughtered within the institution for staff to carry the meat and pay at the end of the month or deducted from their salaries, they are brought en masse to the market for dealers to buy. The animals are priced collectively across the board which are usually sold at cheaper prices compared to that of other agents since these are government-owned farms which is believed to be no body’s property.

Membership of market association: (Table 2b) shows that, there is a well organized and long existing cattle dealers’ association in the study area. The association has its financial members consisting of all traders especially Brokers, Retailers and Dealers who must be duly registered. The association, also, has it executive members, like any other association, registered with the Cooperate Affairs Commission. It has its Chairman, Secretary, Financial Secretary, Treasurer and PRO, who are duly elected. The importance of this association is to serve as a platform for sharing experiences, identifying and solving common problems in relation to the business. (Table 2).

Another important reason for this association is to establish and promote thrift cooperatives which are the major source of credit/loans for the marketers. The most important reasons for marketers joining the market association are: access to soft loan/credit, social interactions, ethnic affiliations, business experience/information sharing (in that order). It is noteworthy that, the market association provides a rallying point for members during social occasions. The results also buttressed the earlier reports of[35,44] in Southern Nigeria.

Production systems: The results in (Table 2c) show that, seventy five percent (75%) of the animals sold or bought in Mubi international cattle market are produced by pastoralists in a traditional way. This implies that, pastoralists constitute a major socio-economic group in the country[45]. These nomads own more than 93% of the country’s estimated 15.3 million cattle population[2]. Pastoralist livestock industry is therefore, the country’s reservoir of animals for slaughter, milk, manure production as well as draft power[46]. The animals are brought to the market mostly by hooves from all over the northern states of Nigeria, neighboring and other countries like Chad, Cameroon, Central Africa, Niger, Mali and Senegal.

However, fifteen percent (15%) of the animals parading the market are produced through home fattening using crop residues, by-products, kitchen waste and left-over food, while ten percent (10%) come from institutions of higher learning who keep animals for research and teaching purposes. The animals from this group are usually eye catching and attract higher prices because of their shining looks and good body condition scores.

Transportation system: The results indicate that, transportation of cattle to the market is usually on hooves (40%) and by vehicles (60%), as shown in (Table 2d). Animals from longer distances, especially those coming from the neighboring countries through the bush are moved on hooves for days or weeks before arriving on Tuesday or Wednesday. While animals produced nearby along motorable roads and those who the owners can afford the transport fare are conveyed to the market by vehicles, the sick and old animals that cannot trek are, also, transported by vehicles such as trucks and pick-up vans as shown in (Figures 3,6,7). The results, also, corroborated that of[41], who reported similar findings in Mubi South LGA, Adamawa State, Nigeria[36]. Fenn also indicated that, marketing of cattle involves variety of transportation methods such as road, rail, ship and air. This depends to a large extend on the road network and reliability of the roads that link producers to the market towns[47]. Akinwumi also observed that, the distance covered, type of vehicles used, the number of animals carried and security checkpoints all together affect transportation cost.

But because of the non-functionality of the rail system, road transporters charge heavy fares since they know there is no alternative for moving cattle to the southern markets. Nigerian cattle marketers have not yet started using air and water transportation system to convey their animals to the markets. The choice of vehicle type depends on the number of cattle to be transported. In certain situations, 3 to 5 dealers buying cattle from the same market join together to hire the articulated trailers and share the cost. When this happens, the animals are branded with unique trademarks which tell which dealer owns which animal. Cost is usually shared in accordance with the number and size of cattle owned by each dealer. Transportation cost are found to vary with distance covered. According to the sources, other factors which can influence transport cost include the size of cattle, the number carried by each vehicle and the season of movement. Usually transport costs are slightly higher during the high demand periods of religious festivities. The results also support[35], who reported similar findings in Southern Nigeria.

Source of capital: (Table 2e) shows that, fourty five percent (45%) of the marketers get capital from their personal savings, fifteen percent (15%) from friends and relations, twenty five percent (25%) from Banks, while fifteen percent (15%) from cooperatives. The results also agree with[35], who reported similar findings in Southern Nigeria. The amount and source of capital to start the cattle marketing business with, is an important issue to consider. This is because, how much an individual marketer has and the source of his capital determines state of his business. This also, influences his relationship with others and the financial institutions in Nigeria. People tend to show more loyalty and trust to well established marketers who invest huge amounts of money into the business. The general public, government and financial institutions have more confidence in those marketers that have their investments running into millions of naira. This category of individuals can single-handedly charter one or more trucks to convey the animals to the southern markets. They can afford the money to clear the road, pay tax and still sustain the business even when they encounter tragedy such as armed robbery and accident resulting to loss of animals and lives. They are the marketers that have access to bank loans because of their influence, connections and their ability to fulfill the loan requirements.

On the other hand, the small scale (low capital) agents operate under the support of the Buzau’s who have gained ground and have sound footings. This class of marketers fined it difficult to access bank loans because of the stringent conditions of Nigerian banks such as provision of guarantors, collaterals and exorbitant interest rates. In the Nigerian business environment, the rich continue to get richer while the poor continue to get poorer, because the Nigerian banking policies do not favor the small and medium scale entrepreneurs.

Factors Considered in Cattle Price Formation

The results show that, there are twenty three (23) phenotypic traits buyers put into consideration before arriving at an agreed price of animals in the study area, as shown in Table 3. Market prices of cattle in Mubi are determined by visual evaluation which incorporates elements of all these factors. But, the price indicators viewed as necessary and very important include breed, age, sex, color, body condition score, temperament, anus stain, and all these depend to some extent on the purpose of buying.

Breeds are ranked or valued high according to their popularity and utility. White Fulani (Bunaji), for instance, are generally accepted to be superior to all other breeds of Zebu because of its ability to resist diseases and thrive under a variety of conditions[48]. The White Fulani cattle are also, important for their genetic predisposition of hardiness, heat tolerance and adaptation to local conditions. The breed is a triple-purpose animal, it may be fattened for beef, kept for milk production, or used as draught animal, especially the bull. They provide much of the beef consumed throughout Nigeria[49]. Ages and sexes of animals are viewed very important in cattle marketing depending on the purpose of purchase. Marketers buying animals as replacement stock go for younger bulls and heifers. While marketers buying for slaughter or shipment down South go for adult well fed animals which attract higher prices. Older cattle have less fat cover on their backs, while bulls have higher BCS compared to old cows[50]. A cow’s reproductive performance is closely associated with her age and body energy reserves. Similarly, cows with low body condition scores have reduced fertility rates, milk yield, late post-partum estrus and low weaning weights[51]. Higher body condition scores precede higher dressing out percentage with good quality meat which, also, attracts greater market values.

Color influences price determination because of belief and the effect of albeddo in relation to animal’s physiological status. It was gathered that, coat color contributes to physiological adaptation in cattle and mediates response to thermal stress. Cattle with light colored silk coats absorb less heat from the environment than dark colored woolly-coated. Coat color is a qualitative trait and an indicator of genetic superiority or productive adaptability of animals to heat tolerance. The results support[52,53], who reported similar findings in Southern Nigeria. Temperament is the posture (docileness or aggressiveness) of an animal, especially, in the market place where danger is sensed. Some animals appear hostile and wild making them difficult to control and handle especially in a strange over crowded environment, while others look cool and docile, which can be easily controlled and handled by even strangers and children. This trait also, affects price of the animal, depending on the purpose of buying. For those buying for slaughter, temperament will not pose much threat. But for farmers buying to replace the old stock, it’s a serious concern to have such an aggressive animal. Anus stain reflects a sign of diarrhea or ill-health. An experienced producer would not worry much about that because he/she knows what to give to the animals immediately the animal is taken home.

Butchers, also, would not bother as the sign of diarrhea will not stop him from slaughtering the animal. Other factors like reproductive organ, eye, nose, ear, mouth, tail, horn, height, width though important have no much effect on the final dressing out percentage. It is only those buying for grazing as breeding stock that would consider all these factors. Breeding stocks need well developed reproductive organs including mammary glands to be able to produce enough milk for the young ones. They also need sound footings to carry their unborn fetuses while grazing. Festivities demand and supply and production system, also, influence prices of these animals. Pastoralists don’t go for animals fattened at home as replacement stock because those home fattened animals are not used to grazing and most of them have over-grown hooves that will not allow them free movement in the bush. It is observed that, an animal is valued for its quality and utility attributes which buyers evaluate when making a purchase decision. Hence, the observed market price for an animal is the sum of the implicit prices paid for each quality attributes. However, in most empirical studies, the observed prices may reflect not only consumer preferences but also attributes of buyers and sellers. The market price of different types of animals is the final price buyers are willing to pay for each quality attribute that enhances utility, the socio-economic attributes of sellers and buyers and the political organization of the market setting. The results concur with the earlier studies of[13,16,41], who reported similar findings in Nigeria (Table 3).

Table 3: Ranking of Factors Considered in Buying and Selling (Pricing) of Cattle.

| Factors | VI (4) | I (3) | SI (2) | NI(1) | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | + | 4 | |||

| Age | + | 4 | |||

| Sex | + | 4 | |||

| Color | + | 4 | |||

| Body conformation | + | 4 | |||

| Height | + | 3 | |||

| Width (size) | + | 3 | |||

| Eye/ear/nose/mouth | + | 3 | |||

| Leg | + | 3 | |||

| Reproductive organ | + | 3 | |||

| Horn | + | 2 | |||

| Tail | + | 2 | |||

| Temperament | + | 4 | |||

| Posture | + | 2 | |||

| Anus | + | 4 | |||

| Purpose of buying | + | 4 | |||

| Purpose of selling | + | 4 | |||

| Festivities | + | 3 | |||

| Demand and supply | + | 3 | |||

| Production system | + | 3 |

VI = very important, I = important, SI = slightly important, NI = not important

Constraints faced by cattle marketers

(Table 4) shows some of the constraints identified to affect cattle marketers in the study area. All the problems are viewed as crucial and constitute bottlenecks in cattle marketing business. There is lack of adequate means of disseminating marketing information to both the producers, sellers and buyers because majority of actors reside and are based in remote areas, where telecommunication services are seriously lacking. They come to cities or market towns only during market days to do their transactions and retire back to the villages. Only few of the marketers who stay in towns and cities have access to telecommunication and regularly get in touch with those in the Southern markets and have enough information on the current state of things in the Nigerian markets. The primary producers are left in the dark and are convinced to take any price given to them, usually lower than what is expected, because the producers do not have relevant information on the market. Though recently, with the advent of GSM, marketers are able to pass vital marketing information across to one another. The market integration, government’s livestock marketing strategies are also yielding the desired result. The numerous cattle markets (Ticke) located all over Nigeria are bringing the Fulanis closer to the community. For example, the Fulanis are now exchanging livestock with horticultural produce and hardware. The markets are an important avenue where the Fulanis and farmers are sharing information about pastoral and agricultural innovations. Markets have, also, become the place for learning about governmental policies. The Fulani’s are using markets for social interaction such as conducting meetings, marriage arrangements and settlement of disputes.

Table 4: Constraints Faced by the Cattle Marketers.

| Problems | I(3) | NI(1) | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate market information | + | 3 | |

| Trickiest way of market intermediaries | + | 3 | |

| High transportation fare | + | 3 | |

| Lack of infrastructure in the market | + | 3 | |

| Lack of credit facilities | + | 3 | |

| Fluctuation in demand and supply | + | 3 | |

| Cattle rustling and buying of stolen animals | + | 3 | |

| Lack of adequate security within the market place and on the roads | + | 3 | |

| Payment of heavy taxes and clearing of roads | + | 3 |

I = Important, NI = Not important

The intermediaries, who are usually seen as greedy people, suffocate the market by over-charging the consumers and under-paying the producers and also influence the price of beef. In the study area, the value of an animal is determined by visual and tactile examination. Scales are seldom used. The sellers and the buyers prefer appraising the animal by their physical appearance. Combining their business acumen and extortion, these cattle traders have become wealthier and more influential than the primary producers. These mediators, most of them non-Fulanis, maintain a large network of representatives. They have chains of markets within and beyond Nigeria. The middlemen, who receive three to five percent sales commission (la’ada), perform the important task of transporting the animals to the market, protecting the herds from bandits, and ensuring that contractual obligations between the sellers and the buyers are fulfilled. At the village level, the cattle producers take the herds to the brokers. Sometimes, however, the brokers themselves go to the encampments to buy the animals directly from the producers. An animal may change hands up to three times before reaching the slaughter slab. Through trading, good relationships based on trust have developed between the producers and the cattle brokers, despite the exploitation of the former by the latter. Transportation of cattle to the Nigerian markets are faced with so many issues, especially the movement of cattle on hooves results in frequent thefts, straying, accidents and transit mortalities. During the journey, the Fulani men whip, traumatize and subject the animals to walking up to twenty to thirty kilometers a day with little time to graze or drink water. Animals arrive markets in a very bad or poor state with many of them too weak to stand and have to be slaughtered immediately. Cattle lose up to forty to fifty percent of their weight in such a long journey of 288 kilometers from Northern Nigeria to Southern Nigeria. The results are in agreement with[54] Kefyalew and Addis (2015), who reported similar findings on beef cattle marketing and illegal trading in North-Western Amhara, Ethiopia.

But by vehicle, it takes just one to two days to drive animals from the North to the Southern markets with minimal lose of weights. The speed of road haulage has resulted in an over-supply of cattle in the Southern markets, leading to a beef glut and a fall in cattle prices. The Fulanis or producers, who do not own the vehicles, rely on the middle-men to haul the herds. Important in distinguishing merchantable stock are transporters who may be more important than the primary producers in cattle marketing. Though the services offered by these freighters are inexpensive considering the huge cost of fuel, vehicles and spare parts in Nigeria, especially the North. Animals transported by vehicle face a number of difficulties throughout the journey. Animals are kept standing, without food or water and most rural roads are seasonal and inoperable during the greater part of the year. Trucks are few and are operated for extended hours which are prone to accidents because they are overloaded and travel on laterite. In the absence of functional insurance schemes in Nigeria, some Fulanis or producers are reluctant to use road haulage for lack of safety. The government policies of providing infrastructure and credit facilities such as the extension of roads that will link rural producers with urban consumers, provision of fences, scales, grains, freight facilities, feed lots, meat markets, retail sheds, fattening centers, grazing spaces, veterinary inspection at the livestock evacuation centers and cooperative societies are weak and non-functional.

The seasonal availability of herds, the prevailing environmental conditions, the demand for cash, and the price of stock affect the quantity of animals the Fulanis or producers take to the markets. Animals reach their highest prices during the rainy to early dry seasons when they are fattest. Livestock sales peak during droughts, epidemics, or dry-seasons when selling becomes as much a way of getting rid of sick stock as it is of balancing herd size with water and pasture availability. Livestock dealers report the influx of sick and impoverished animals during famines or epidemics, resulting in beef glut.

The Fulani’s sell animals to buy salt, cloth, food, and animal feed. They, also, sell to buy luxury goods such as radios, bicycles, motorcycles and furniture. In some cases, the motive is to trade a bull to buy two or more calves, to marry, or to go to Mecca for pilgrimage. An urgent demand for cash may compel the marketing of an animal. The Fulani cattle-owners use sales proceeds to pay school fees and fines for crop damage, and pay taxes, as it were in the past. The purchase of household needs and the meeting of important social and religious commitments are strong reasons for a Fulani man to take his animals to the market. There are, also, many cases of cattle rustling and marketers buying stolen cattle, landing them into Police net. Cattle are snatched at gun point on transit and armed robbers storming the cattle markets, carting away millions of naira belonging to marketers. The recurring insecurity in many parts of the country involving cattle movement has resulted in the frequent ethnic clashes where the Fulani and crop farmers continue to kill themselves without mercy. Recently, newspapers have reported disruption of cattle movement to the East as a result of the crisis in the middle belt. It is also, obvious that, the escalation of animosity against the Fulani by southern tribes have forced a reduction in commercial activities in the cattle markets. At one time, for instance, the Fulani and the cattle brokers threatened to close the cattle market in Enugu and move it northward to Makurdi, if attacks on the Fulani and their cattle continue in the South-East which also affects the marketers and consumers as well.

The heavy taxes leveled against the cattle marketers and incessant exploitation by security agents on our high ways call for serious worry. These security outfits know all the market days and even are familiar with feeder roads linking each village to the main market town. They collect an average of two to five hundred naira per vehicle loaded with cattle to Mubi international cattle market. Marketers spend two to three hundred thousand naira just for road clearance from the North to the South. All these impediments have gross negative impact on the producer and the final consumer, who are always left unfulfilled.

Conclusion

Cattle marketing in Mubi South L.G.A. of Adamawa State are predominated by experienced, married, male Hausa-Fulani Muslims aged, mostly, 20 – 50 years. The marketers have limited western education, indicating limited change in the socio-cultural status of actors in the face of a rapidly changing marketing environment, exemplified by the shrinking facilities and capital resources. Cattle marketing dynamics involves production, fattening, buying, selling, brokering, retailing, dealing, transporting and butchering. It is, therefore, concluded that, marketing of cattle in the study area is a profitable venture if special consideration is given to tackle the bottlenecks militating against the smooth transactions and efficient marketing processes.

Recommendations

The following recommendations were made to aid in improving the cattle marketing dynamics in Mubi South Local Government Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Government should intensify efforts to encourage cattle production by providing modern breeding facilities such as AI stations, loan or credit incentives through commercial banks. Security outfits should be established in the market to prevent the problem of theft, marketers should form strong organization to see that, any strange or suspected person that brought cattle to the market is strictly scrutinized before selling. Local Government Council should assist in formation of a body charged with the responsibilities of passing information to producers and marketers on the supply, demand and price of cattle in the market. Government should encourage the herdsmen to settle in one place by establishing grazing reserves, range land or pasture lands. There is need for the provision of modern cattle marketing facilities like standard weighing scales, loading spaces, and grades in the markets to help in transforming the market from the current traditional system. Government should provide more veterinary facilities to minimize incidence of diseases and parasites. Cattle should be properly checked before buying and selling. Quarantine stations should be located in strategic places to prevent diseased animals getting into the market.

References

- 1. Ikpi, A.E. Livestock Marketing and Consumption in Nigeria from 1970-1989

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 2. Tibi, K.N., Aphunu, A. Analysis of Cattle Market in Delta State: The Supply Determinants. (2010) Afr J Gen Agric 6(4): 199-203.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 3. Abubakar, I.A., & Garba, H.S. A Study of Traditional Methods for Control of Ticks in Sokoto State. (2004) Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Nigerian Society for Animal Production 29: 87-88.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 4. Mafimisebi, T.E., Oguntade, A.E., Fajeminsin, N.A., et al. Local Knowledge and Socio Economic Determinants of Traditional Medicines’ Utilization in Livestock Health Managements in South West Nigeria. (2012) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 8: 2.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 5. Annual Report of Central Bank of Nigeria. (1999) CBN.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 6. Adegeye, A.J. Statistical Analysis of Demand for Beef in the Western State of Nigeria. (1975) J Rural Economics Develop 9(1): 3-13.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 7. Okunmadewa, F.Y. Livestock Industry as a Tool for Poverty Alleviation. (1999) Trop J Anim Sci 2(2): 21-30.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 8. Trypanotolerant Cattle and Livestock Development in West and Central Africa, FAO. (1987) Anim Product Health Paper 2: 67/2.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 9. Tewe, O.O. Sustainability and Development: Paradigms from Nigeria’s Livestock Industry. (1997) Inaugural lecture series.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 10. Tukur, H.M., Maigandi, S.A. Sustainability and Development: Paradigms from Nigeria’s Livestock Industry. Characterization and Management of Animals used For Draught. (1999) Trop J Anim Sci 1(1): 10-27.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 11. Mafimisebi, T.E., Okunmadewa, F.Y. Are Middlemen Really Exploitative? Empirical Evidence from the Sun-dried Fish Market in Southwest, Nigeria. (2006).

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 12. Umar, A.S.S., Alamu, J. F., Adeniyi, O.B. Economic Analysis of Small-scale Cow Fattening Enterprise in Bama Local Government of Borno State, Nigeria. (2008) PAT 4(1): 1-10.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 13. Mafimisebi, T.E. Spatial Price Equilibrium and Fish Market Integration in Nigeria: Pricing Contacts of Spatially Separated Markets. (2011) LAP 157.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 14. Olayemi, J.K. Rice Marketing and Prices: A case Study of Kwara State, Nigeria. (1973) Bulletin of Rural Economics and Sociology 8(2): 211-242.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 15. Olayemi, J.K. Scope for the Development of the Food Marketing System in Ibadan, Nigeria. (1974) FAO Report 1-29.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 16. Seperich, G.J. Woolverton, M.W. Beirlein, J.G. Introduction to Agribusiness Marketing Pearson Education Company.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 17. Kohls, R.L., Uhl, J.N. Marketing of agricultural products, 9th Edition. (2002) Prentice-Hall McMillan Publishers Company New York.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 18. Omoruyi, S.A., Orhue, U., Akerobo, A.A., et al. Prescribed Agricultural Science for Secondary Schools (2000) Idodo Umeh Publishers Ltd 443-445.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 19. Mafimisebi, T.E. Spatial Equilibrium, Market Integration and Price Exogeneity in Dry Fish Marketing in Nigeria: A Vector Auto-regressive (VAR) Approach. (2012) J Econ Finance Adm Sci 17 (33): 31-37.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 20. Umar, A.S. Financial Analysis of Small-scale Beef Fattening Enterprise in Bama Local Government Area of Borno State, Nigeria. (2014) J Resour Dev Manag 3.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 21. Nigerian National Livestock Project Division. (1992) NLPD 58:175-177.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 22. Nigerian National Livestock Project Division. (1992) NLPD 58:175-177.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 23. Adebayo, A.A., Tukur, A.L. Adamawa state in maps. (1999) Paraclete Publishers.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 24. Adebayo, A.A. Climate, Sunshine, Temperature, Evaporation and Relative humidity. (1999) Federal University Tech, Yola 20-22.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 25. Map of Nigeria showing all States. (2010a) Adamawa State Ministry of Land and Survey Nigeria.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 26. Adebayo, A.A., Tukur, A.L. Adamawa state in maps. (1997) Paraclete Publishing company.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 27. Nigerian Electoral Body Responsible for Organization and Conducting General Elections. (1996) Independent National Electoral Commission.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 28. Nigerian Agency Responsible for Conducting Census. (1991) National Population Commission.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 29. Map of Adamawa State of Nigeria showing all Local Government Areas. (2010) Adamawa State Ministry of Land and Survey, Nigeria.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 30. Production Year Book. (1990) FAO Rome 46:153.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 31. Areola, O.O. Soil and vegetational resources. Geography of Nigerian development 342.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 32. Adamawa Agricultural Development Programme. (1986) Method of Vegetable Gardening 3-4.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 33. Mansir, M. Livestock Marketing and Transportation. (2006) Nigeria.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 34. Adebayo, A.A., Tukur, A.L. Adamawa State In maps. (1991) Paraclete 35 - 40.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 35. Mafimisebi, T.E., Bobola, O.M., Mafimisebi, O.E. Fundamentals of Cattle Marketing in Southwest, Nigeria: Analyzing Market Intermediaries, Price Formation and Yield Performance. (2013) Int Conference Afr Assoc Agric Econ 22-25.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 36. Fenn, M.G. Marketing Livestock and Meat. (1977) Animal Production and Health Series No.1, FAO, Rome.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 37. Auwal, A. Political Decisions in Nigerian Agricultural Industry. (2005) J Appl Sci Manag 2: 186.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 38. Iro, I.S. The Fulani herding system. (1994) Afr Develop Found USA.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 39. Swinton, S. Drought survival tactics of subsistence farmers in Niger. (1988) Human Ecology 16(2): 123-144.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 40. Burns, J.A. Marketing of Agricultural Products: Kohls, R.L., Uhl, J.N Sixth Edition (1985) McMillan Publishers.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 41. Mubi, A.A., Michika, S.A., Midau, A. Cattle marketing in Mubi Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria. (2012) Agric Biol J N Am 4(3): 199-204.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 42. Wakili, B.A. Connection and Profit Margin of Cattle marketing in Maiduguri. unpublished.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 43. Ajiya, K. Student Final Year Project. Federal University of Technology. (1998) Unpublished.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 44. Akinrinola, O.O., Mafimisebi, T.E. Contributions of Informal Savings and Credit Institutions to Rural Development: Evidence from Nigeria. (2010) J Rural Co-operation 38(2): 187-202.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 45. Moutari, M. Securing pastoralism in East and West Africa: Protecting and promoting livestock mobility. (2008) Chad Desk Review.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 46. Kubkomawa, H.I., Helen, U.O., Timon, F., et al. The use of camels, donkeys and oxen for post emergence weeding of farm lands in North-Eastern Nigeria. (2011) J Agric Soc Sci 7(4): 136-138.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 47. Akinwumi, J.A. A Proceeding of Workshop on the Proposed Sub-Livestock Sector Review Held in Jos. (1986) The Nigerian Livestock Industry (Problems and Prospects).

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 48. Meghen, C., MacHugh, D.E., Sauveroche, B., et al. Characterization of the Kuri Cattle of Lake Chad using Molecular Genetic Techniques. (1999) The origin develop African livestock 28-86.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 49. Alphonsus, C., Akpa, G.N., Barje, P.P., et al. Comparative evaluation of linear udder and body conformation traits of bunaji and friesian x bunaji cows. (2012) World J Life Sci Medical Res 2(4): 134-140.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 50. Joe, C.P. Using body condition scores in beef cattle. (2010) Livestock Specialist Texas Agrilife Extension.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 51. Clay, P.M., Jason, E.S., Ron, K. Managing and feeding beef cows using body condition scores. (2002) New Mexico State University.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 52. McManus, C., Prescott, E., Paludo, G.R., et al. Heat tolerance in naturalized Brazilian cattle breeds. (2009) Livestock Sci 120(3): 256-264.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 53. Fadare, A.O., Peters, S.O., Yakubu, A., et al. Physiological and haematological indices suggest superior heat tolerance of white-coloured West African Dwarf sheep in the hot humid tropics. (2013) Trop Anim Health Prod 45(1): 157-165.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 54. Kefyalew, A., Addis, G. Beef cattle marketing and illegal trading in North Western Amhara, Ethiopia. (2015) Dyn J Anim Sci Technol 1(2): 43-48.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others