Maternal And Neonatal Outcome In Pregnancy With Large Gynaecology Tumour

Bismarck Joel Laihad, Christian Homenta, Glenn Christian Rarung

Affiliation

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Sam Ratulangi University, North Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Corresponding Author

John Johannes Wantania, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prof. Dr.R. D. Kandou Manado General Hospital, Sam Ratulangi University, Jalan Raya Tanawangko, No. 56, Manado, Sulawesi Utara,Indonesia. Tel: +62-81356023456; E-mail: john_w_md@yahoo.com, john_w_og@yahoo.com

Citation

Wantania, J.J., et al. Maternal and Neonatal Outcome in Pregnancy with Large Gynaecology Tumour (2015) J Gynecol Neonatal Biol 1(2): 21-27.

Copy rights

©2015 Wantania, J.J. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Keywords

Outcome, Pregnancy, Large gynaecology tumour

Abstract

Gynaecological tumour in pregnancy is a complex problem that requires the expertise of multidisciplinary task force. The tumour mass may be asymptomatic and unintentionally found or may be undetected until it reached a voluminous size and occupied the abdominal cavity. Most of gynaecological tumours in pregnancy are diagnosed unintentionally during visits or during first trimester ultrasound screening. Although the data are conflicting and most women with a large sized ovarian cyst in pregnancy may be complicated by torsion, rupture, haemorrhage, infection, as well as obstruction in delivery. And women with a large sized fibroids have uneventful pregnancies, the weight of evidence in the literature suggests that uterine fibroids are associated with an increased rate of spontaneous miscarriage, preterm labor, placenta abruption, malpresentation, labor dystocia, cesarean delivery, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Individual treatment is the main issue when gynaecological tumour is diagnosed during pregnancy. When faced with the problem of gynaecological tumour in pregnancy, a thorough evaluation and avoidance of emergency procedure hazardous to both mother and the baby is needed. The treatment of a gynaecological tumour during pregnancy should be based on stage of pregnancy, the nature of the tumour, individual symptoms, safety of the foetus, and considering the fertility of the patient after treatment. Treatment should be given to maximize the survival rate and at the most proper time point.

Introduction

Worldwide prevalence of tumour shows that gynaecological tumour such as tumours in the vulva, cervix, uterus, ovarian, and fallopian tube are 19% of the 5.1 million tumour cases found in 2002 and gynaecological tumours is 22% of all tumours in women in developing countries, compare to that of 15% in the developed countries[1].

Ovarian tumour is rarely found during pregnancy[2-4]. In a Canadian large scale survey, it was found that the incidence of malignant ovarian tumour is 0.041 per 1.000 pregnancy, most of them are borderline tumours, followed by epithelial tumour[5-9]. In Europe and in the United States, the incidence is 0.04 – 0.11 per 1.000 pregnancy, and most of them are borderline tumours[5]. In Asia, the incidence is 0.106 per 1.000 pregnancy, 40% of them are borderline tumours[6].

Incidence of adnexal mass during pregnancy ranges from 1 per 81 pregnancies to 1 per 8000 pregnancies[10]. The increased incidence of diagnosed ovarian cyst during pregnancy was due to the use of ultrasound examination during the first trimester as well as due to the increase of induction of ovulation. This increase the level of anxiety in pregnant women in whom the likelihood of detected tumours also increases with age[11]. The most common types of ovarian cyst are dermoid cyst (25%), luteal body cyst, functional cyst, paraovarian cyst (17%), serous cystadenoma (14%), mucinous cystadenoma (11%), endometrioma (8%), carcinoma (2.8%), low potential malignant tumour (3%), and leiomyoma (2%)[12]. Complications of cysts related to pregnancy includes torsion, rupture, infection, malignancy, cyst impaction on pelvis, causing urine retention, obstruction of delivery, and malpresentation of foetal position.

Uterine fibroid or uterine myoma is the most common pelvic tumour in women. Uterine myoma occurs in 25 –40% women in reproductive age[13]. Recently there was a 2 – 4% increase in the incidence of uterine myoma during pregnancy due to more women elected not to have children until their late thirties or early forties, increasing the risk of uterine myoma development[14,15]. Uterine myoma generally occurs in women more than 30 years of age, and the growth of uterine myoma tissue is directly related to the exposure of circulating estrogen[16-18]. The effective prevalence of uterine myoma is still unknown but it causes various complications in both the mother and the baby, including: spontaneous abortion, premature labour, placental abruption, postpartum bleeding, and the increase of caesarean section incidence[15,19].

The complications of pregnancy and labour are doubled in pregnant women diagnosed with uterine myoma, compare to women with no uterine myoma[16,17]. Literatures showed that the incidence of caesarean section in women with uterine myoma is as high as 39 – 95%[20]. Coronado et al., conducted a population based serial study in 1987 to 1993 in Washington to women who gave birth to a single living infant[20]. The study found an independent correlation between uterine myoma and the incidence of placental abruption, foetal malpresentation, dysfunctional delivery, and breech presentation. The author also found a 58% increase in the risk of caesarean section in 2,065 women with uterine myoma in pregnancy, compared to 4.243 women with no uterine myoma (odds ratio [OR] 6.39, 95% CI 5.46 – 7.5). The risk may increase due to the fact that uterine myoma may be found incidentally during caesarean section. On the other hand, complications such as placental abruption, dysfunctional delivery, and breech presentation were generally treated through caesarean section, indicating that the high cost may be due to the leiomyoma itself[20].

We presented a rare case report of a large sized gynaecological tumour in term pregnancy, i.e. ovarian tumour with more than 30 cm diameter and uterine myoma with more than 20 cm diameter.

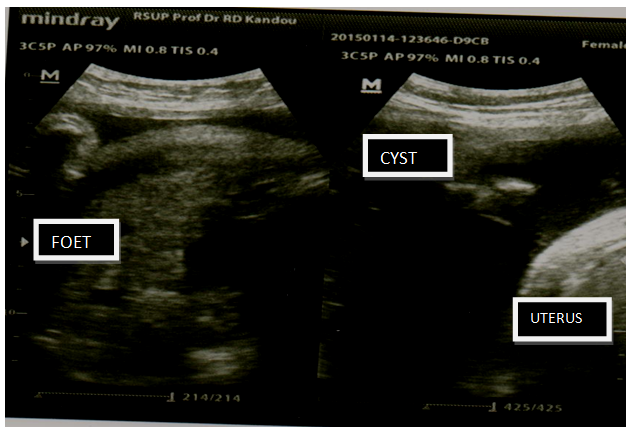

Case Report I

Mrs PK aged 28 years old visited the Obstetric Outpatient Clinic of Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado General Hospital for an antenatal care on October 31, 2014. The patient was diagnosed with G2P1A0 28 years old, gestational age 39-40 weeks, not in labour, with large sized ovarian cyst; foetus was intrauterine, single, living, breech presentation + macrosomia. Physical examination was found to be within normal limit. In the obstetric examination, it was found that foetal presentation was breech presentation, foetal heart rate was 145 seconds/minute, negative contraction. A cystic mass was found on palpation, with the size comparable to that of a soccer ball, in the fundus area. Ultrasound result came back with an intrauterine foetus, breech presentation, and the estimated foetal weight is 4000 gm. There was an anechoic homogenous feature next to the uterus, filling the abdominal cavity, septa (-), papil (-) (Figure 1). Laboratory examination result came back with 12.9gr/dl haemoglobin, 7.500/mm3 WBC, 232.000/mm3 platelet. Liver and kidney functions were within normal limit. Ca 125 was found to be 17.5 U/ml.

Figure 1: Ovarian Cyst

On November 4, 2014 the patient underwent a caesarean section and left salphingo-Oophorectomy with spinal anaesthesia. After the peritoneum was opened, a 30x30 cm left ovarian cyst was found, with smooth surface and no adhesion. Before the caesarean section, a decompression was first conducted on the left ovarian cyst, approximately 10 litres (Figure 2). Caesarean section was then performed, and the patient delivered a female baby with birth weight of 4000 gram, birth length of 50 cm, and Apgar score of 8-10. After the uterus was stitched, a left salphingooophorectomy was then performed. The duration of surgery was approximately 1 hour and 10 minutes. The patient’s postoperative general condition was well, and her vital signs are within normal limit

Figure 2: 30x30 cm Ovarian Cyst Decompression

The patient was the followed up in the regular ward for 3days. On November 10, 2014, the patient visited the Gynaecology Outpatient Clinic of Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado General Hospital for a follow up visit. During this visit, the patient presented her Pathological Anatomy examination result, and the reading came back with a serous ovarian cyst.

Case Report II

Mrs DA, aged 34 years old, visited the Obstetric Outpatient Clinic of Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado General Hospital for an antenatal care on December 4, 2014. After a thorough examination, the patient was diagnosed as 34 years old G1P0A0, gestational age of 37-38 weeks, not in labour, with large sized uterine myoma; the foetus was intrauterine, single, living, with breech presentation. Physical examination was within normal limit. In the obstetric examination, it was found that the foetal presentation was breech presentation, and the foetal heart rate was 135seconds/minute, negative contraction. A supple solid mass was palpable in the fundus area, with a size comparable to that of a baby’s head. Ultrasound examination was then performed, with a result of an intrauterine single foetus with breech presentation, and estimated foetal weight was 2765gm. The reading was suggestive of term pregnancy. A fibroid feature was found in the anterior corpus area, extending to the fundus, with an approximate size of 22 x 21 cm. Laboratory examination came back with 10.2gr/dl haemoglobin, 7.900 /mm3 WBC, 268.000 /mm3 platelet. Liver and kidney functions were within normal limit.

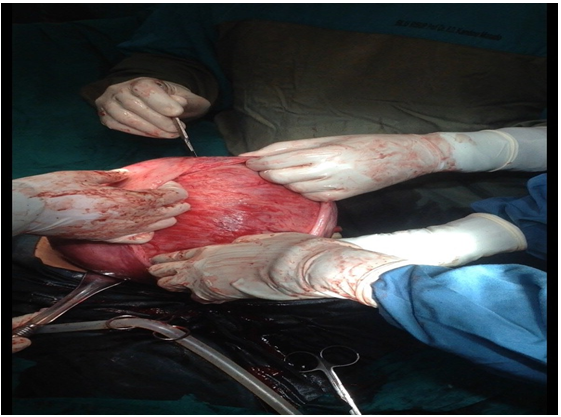

On December 8 2014, a caesarean section was performed with spinal anaesthesia. During the caesarean section, a seromural uterine myoma was found on the anterior corpus area, extending to the fundus. The size was approximately 20 x 20 cm (Figure 3). After a female baby with birth weight of 2800 gram, birth length of 48 cm and 6-8 apgar score was born, it was decided to proceed with a myomectomy. Before the myomectomy was performed, a 16 Foley catheter was inserted to function as a tourniquet for the lower uterine segment at the level of the uterine artery to control bleeding. An enucleation was then performed on the fibroid tissue. The uterine wall was stitched layer per layer, with interrupted suture to prevent dead space. The serous uterine tissue was stitched using a running baseball technique (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Enucleation of 20 x 20 cm, 3 kg seromural Uterine myoma

Figure 4: Running baseball suture on the serous Uterine tissue

The surgery duration was 1 hour and 30 minutes. The patient’s postoperative general condition was well, her vital signs were within normal limit. Six hour postoperative laboratory examination came back with 8.5gr/dl haemoglobin, 17.500 / mm3 WBC, 253.000 /mm3 platelet.

The patient was then followed up in the regular ward for 3 days. On December 5 2014, the patient visited the Obstetric Outpatient Clinic of Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado General Hospital for a control visit, presenting her pathological anatomy examination result, whose reading came back with a uterine myoma.

Discussion

As of today, the cause of ovarian cyst is still not fully understood; however, a few theories mentioned a disruption in estrogen formation and in the ovarian-hypothalamic feedback. Patients may be asymptomatic with no indication that the tumour may disrupt the foetus growth and development. Large sized tumour may, in some cases, hinder the uterus growth, resulting in premature labour or abortion. Clinical diagnosis of early stage ovarian tumour relies on bimanual palpation and ultrasound examination. If the tumour is fast-growing, it may manifest as nausea, abdominal pain, palpable mass, and other symptoms of compression.

Pelvic ultrasonography is the best method to detect ovarian tumour, its position, size, shape, adhesion to uterus, as well as the presence of a cystic liquid and a free liquid inside the pelvic cavity. If pelvic mass was found during pregnancy, a follow up examination with an ultrasound may help to determine the development of the mass. This mass should be observed dynamically with an ultrasound. The majority of ovarian cysts are follicular cyst or luteal body cyst, with 5 cm diameter (rarely reached 10 cm). Ninety per cent of functional cysts may disappear as the pregnancy progresses and may disappear completely at 14 weeks gestational age. Six per cent of the cysts are less than 6 cm, and 39% of them with the size of more than 6 cm, may still be found after 14 weeks gestational age. A cyst of more than 15 cm diameter was reported to be 12 times more probable to become malignant compare to cysts with less than 6cm diameter[21]. In this case, ultrasound examination found a cystic mass of more than 15 cm, and its circulation was indicative of a benign tumour. It remains to be noted that a diagnosis based on ultrasound is limited by the clinician’s or the sonograph’s experiences and it may be blocked by the abdominal organs during pregnancy, which in turn may result in misdiagnosis.

CA-125 is widely used as a marker of ovarian tumour epithelial, with 80% positive detection rate in most of serous ovarian adenocarcinoma cases. However, CA-125 is not specific for ovarian tumour, and the level of this marker is normally increased during pregnancy. If ovarian tumour was detected by pelvic ultrasonography and CA-125 in blood increased, surgical intervention in early second trimester and the pathology result will be very beneficial. The follow up using combination with other biomarkers can be considered. When elevated, the CA-125 can provide a baseline value before treatment of ovarian cancer but will not help differentiate between benign and malignant masses during pregnancy. Although germ cell tumours are among the most common ovarian malignancies seen in pregnancy, both hCG and AFP have very limited use as tumour markers during pregnancy. Tumour markers should be obtained before any surgical intervention when there is a suspicion of ovarian malignancy to provide a baseline, should a malignancy be diagnosed? Any elevation in the tumour markers should be considered in conjunction with the results of the imaging tests.

The routine use of ultrasound in early pregnancy may result in early diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic ovarian tumour. These tumours are rare, with complications such as torsion, rupture, haemorrhage, preterm delivery, and other prenatal effects to the foetus. Complications usually occur during the third trimester. Ovarian torsions or adnexal torsion may be partial or full from the ovarian vascular pedicle, causing an obstruction to the venous and eventually arterial blood flow. Ovarian torsion occurs mainly to women in reproductive age, and rarely (3%) in gynaecological emergency cases. The diagnosis is based on the high index of clinical suspicion and the result of ultrasonography. The cyst may be ruptured due to trauma, such as falling or spontaneous labour, especially if the cyst is located inside the pelvic cavity and was pressed by the descending foetus head or by the termination of delivery[22].

The treatment would be performed when a persistent or larger sized ovarian mass was found, because such mass would increase the risk of acute abdomen, ovarian torsion, or rupture[23]. When an ovarian cancer is found, treatment should be individualized, considering the type and degree of cancer, maternal preference to continue pregnancy, as well as the risk of delay and modification of treatment.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in a guideline stated that, “a simple, unilateral, unilocular ovarian cyst, with less than 5 cm diameter is of low malignancy risk”. If the serum CA125 is normal, the cyst may be treated conservatively[24].

The detrimental consequences for both the mother and the baby are due to the complication of ovarian mass or mass intervention. If an ovarian malignancy is present, there is a concurrent risk of cancer as well as its treatment and consequences. In literature review, it is often difficult to determine whether the detrimental effects are due to the adnexal mass, mass treatment, or other unrelated issues (such as spontaneous abortion of foetus with multiple anomaly in patients with ovarian mass). However, surgical intervention for benign adnexal mass in pregnancy is correlated with the increase of preterm delivery risk and low birth weight compare to that of patients not undergoing surgical intervention[25]. Pain is the most common symptom in pregnant patients with adnexal mass (26% in Struyk’s study)[26]. It ranges from mild to severe (requires emergency laparotomy). The etiology of pain is usually due to torsion, although ovarian rupture may also occur. Whitecar reported that almost half of the patient with acute abdominal pain required emergency laparotomy for ovarian mass and uterine leiomyoma[27]. The number of torsion is relatively varied, starting from 1% to 22%[28,29]. Rupture occurred in smaller percentage, ranging from 0% to 9% [26,27,29]. Obstruction in delivery was also reported at 2% to17%[26,30]. Other more rare problems include haemorrhage and infection. Struyk recorded the correlation between the size of tumour and complication risks, which is 35% for tumour between 5 and 6 cm diameter, and 85% for larger tumour[26]. However, no author reported high incidence of maternal complication. An American observational study by Bernhard and Zanetta reported a lower complication rate for torsion and obstruction of delivery[31,32].

Detrimental and poor foetal condition is the most common catastrophic abdominal outcome of ovarian torsion or rupture with abdominal surgery. In most cases, the correlation between poor foetal outcome and adnexal mass is unclear. Elective surgical intervention is better performed during the second trimester where the risk of foetal loss may be minimalized[33]. Whitecar found that poor pregnancy outcomes, including preterm labour and foetal loss is even more rarely occur when laparotomy is performed before 23 weeks gestational age (odds ratio 0.15, P 0.005)[27].

Overall, the management of pregnant patients with a malignant ovarian neoplasm is similar to what is recommended in the nonpregnant state. The primary difference lies in considering adjustments in the surgical and/or chemotherapy treatment to allow for foetal viability if the patient desires this. A decision regarding sparing of the intrauterine pregnancy is based on gestational age. In the first trimester, sacrifice of the pregnancy may be the best choice, because exposure to subsequent chemotherapy may be teratogenic. In the second and third trimesters, preservation of the pregnancy is generally recommended because limited clinical experience has failed to demonstrate an adverse foetal effect with chemotherapy given during the pregnancy. A limited delay in the timing of definitive surgical resection or chemotherapy until after delivery is unlikely to result in a worse prognosis unless the patient has obvious metastatic disease[34,35].

Uterine myoma is found among 2-4% of pregnant women, with an increasing incidence due to the fact that more women opting to delay having children[36,37]. One in ten women in this case will experience complication during labour, due to uterine myoma. Most cases of uterine myoma in pregnancy are asymptomatic and not requiring treatment, where 22-32% of them will grow in size[38]. Large sized myoma or fibroid ( >5 cm) tends to develop and enlarge during pregnancy and may cause some issues including abortion, obstruction of delivery passage, foetal malpresentation, symptoms of increased compression, pain due to red degeneration, premature labour, premature rupture of membranes, placental retention, postpartum haemorrhage, and uterine torsion[38-40]. Katz et al. discovered the fact that 10-30% women with uterine myoma during pregnancy experience complications as mentioned above[40].

Pregnant women with uterine myoma have higher rates of caesarean section, reaching as high as 37%, which were generally caused by obstruction of birth passage and malpresentation[37]. Caesarean myomectomy must be considered by an obstetrician if possible on the basis of preserving the uterus without sacrificing its function and not to endanger a woman’s ability to bear another child; this achievement is a more expected achievement in myomectomy than hysterectomy.

Exacoustos and Rosati conducted a case series study in 9 patients undergoing caesarean myomectomy. Three of the patients experienced complication of massive bleeding, necessitating hysterectomy on those patients. Therefore, the authors recommended a cautious approach in deciding to perform caesarean myomectomy[38]. On the other hand, some authors reported high incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and puerperal sepsis when uterine myoma was not removed during caesarean section[40]. In addition to that, immediately after delivery, the uterus will be more easy to adapt physiologically to control bleeding compared with other phases in a woman’s life; thus, caesarean myomectomy may be a logical option.

Until today, the removal of uterine myoma during caesarean section is still regarded as a therapeutic dilemma. In the past, myomectomy during caesarean section was less favoured due to the risk of uncontrollable bleeding, with an exception for cases of pedunculated myoma[41] Latest studies have discussed the techniques that may minimize blood loss in caesarean myomectomy, among them are: insertion of tourniquet during myomectomy, bilateral ligation of the uterine artery, and electrocauterization[42-44]. Some authors have proven that caesarean myomectomy performed in certain patients by an experienced hand is a safe and effective procedure[42,45].

To reduce haemorrhage in caesarean myomectomy, some operators insert a tourniquet around the uterus by bilaterally puncturing the ligamentum latum uterine on the level of internal cervix and by inserting a foley catheter or red rubber catheter through the hole and then tighten the catheter using a clamp to constrict the uterine vessels. The use of tourniquet combined with clamping the vessels, with clamps generally placed on the infundibulopelvicum ligament. Intravenous oxytocin drip is generally administered after the enucleation of myoma (some operators also preferred to administer intravenous drip during myomectomy). The suture on the basis of uterine myoma generally used two-layered interrupted suture (single interuptus) and baseball suture is used on pars serosa as the third layer[46,47].

Kaymak et al. compared 40 patients of uterine myoma who had undergone caesarean myomectomy with 80 patients who had undergone only caesarean section without myomectomy. The average size of uterine myoma removed in the intervention group is 8.1cm and 5.7 cm in the control group. The author did not find any significant differences in terms of haemorrhage (12.5% in caesarean myomectomy group and 11.3% in the control group), post-operative fever, or the frequency of blood transfusion. From the result of those studies, we can conclude that myomectomy during caesarean section is not always dangerous and its complications may be prevented when the procedure is performed by an experienced obstetrician[34].

Ortac et al. reported 22 cases of myomectomy during caesarean section on the indication of large sized uterine myoma (> 5 cm), in which the myomectomy was performed to minimize postoperative sepsis. In another study by Burton et al. on 13 cases of myomectomy during caesarean section, the author only found 1 case of intraoperative haemorrhage and concluded that this procedure is safe for the patients[48].

A large retrospective case control study by Li Hui et al. investigated the effectiveness, safety, complications and outcome of myomectomy during caesarean section on Chinese women with uterine myoma in pregnancy. One thousand two hundred and forty two pregnant women undergoing myomectomy during caesarean section assigned to the intervention group were compared with 3 control groups, including: 200 pregnant women without uterine myoma (Group A), 145 pregnant women with uterine myoma undergoing only caesarean section (Group B), and 51 pregnant women undergoing hysterectomy during caesarean section (Group C). There were no significant differences between both groups in terms of haemoglobin level, frequency of haemorrhage, postoperative fever, or length of stay in the hospital. This findings strengthen the fact that myomectomy during caesarean section is an effective and safe procedure with no significant complications[49].

This fact is further strengthened by a case series study conducted by Hassiakos et al. They compared 47 pregnant women with uterine myoma undergoing caesarean myomectomy with 94 pregnant women with uterine myoma undergoing only caesarean section. The study found a prolonged duration of surgery in the caesarean myomectomy, with an average prolongation of 15minutes. No patient had to undergo hysterectomy, experienced postpartum complications or required blood transfusion in this study. Length of stay in the hospital is not significantly different between these two groups[50]. Therefore, the author generally recommended caesarean myomectomy. Yuddandi et al. reported a removal of 33.3 x 28.8 x 15.6 cm uterine myoma during caesarean section with the amount of loss blood of 1.860 ml, which required blood transfusion[51].

Some author also recommended types of uterine myoma best treated with caesarean myomectomy. Roman and Tabsh recommended that intramural myoma located in the fundus must be avoided[52]. Hassiakos et al. concluded that intramural myoma located in fundus, uterine myoma located in the proximal fallopian tube and uterine myoma located in the cornu must be avoided[53].

For general cases of gynaecological tumour in pregnancy, whether in the form of uterine myoma or ovarian cyst, both the mother and the baby must undergo a standard antenatal care. Problems relating to pregnancy must be treated according to the obstetric standard procedures to achieve a maximum outcome both for the mother and the baby. In obstetric management, especially in women diagnosed with gynaecological tumour in pregnancy, physicians often pay attention to risks on foetal management. Although precautions and attention to the safety of the foetus is very much noted, delaying the effective gynaecological management for the mother is in violation of an important rule of medical ethics: beneficence and non-maleficence.

There is no doubt that pregnancy will not worsen the prognosis of gynaecological tumour during pregnancy. Therefore, all the treatments may be performed during pregnancy. Surgery may generally be performed on both the mother and the baby indication, although the risks are dependant of the procedures. The foetal outcomes itself are dependant of the complications of gynaecological tumour in pregnancy. Increased risk of abortion may occur if the procedure is performed in the first trimester; those risks include malformation or problems in neural development. The risks in the second and third semester include the possibility of foetal death or premature labour. Attention must be given mainly to reduce unfavourable risks for the foetus and neonate due to the surgical procedure[54].

Overall, surgical intervention for all ovarian tumours is better performed in early second trimester, whereas fibroid is better managed before or after pregnancy, although the definitive and commonest treatment modality is still hysterectomy. When myomectomy could be safely done during caesarean deliveries, this could prevent the added morbidity of a separate procedure (laparotomy to remove fibroids, anaesthesia, and its possible complications) in the future, justifying the cost effectiveness of the approach.

In these two cases of large ovarian cyst and large uterine myoma found on term pregnancies, both of them caused foetal malpresentation. In the case of ovarian cyst, a decompression to the cyst was performed before caesarean section. Caesarean section was performed after, followed by left salphingooophorectomy. Whereas in the case of uterine myoma, the caesarean section was followed by myomectomy. The high rate of caesarean section due to malpresentation and the risk of birth passage obstruction was proven in large gynaecological tumours in pregnancy. Surgical intervention for large ovarian tumour during pregnancy will be very helpful and may reduce caesarean section rate due to malpresentation or obstruction in similar cases.

There were no significant morbidities found in both the mother and the baby in the end of pregnancy. In the third day, the mother and the baby are discharged. Followed on the mother and the baby was performed until four months after the surgery, and no anomaly was found.

Conclusion

The management of gynaecological tumour in pregnancy usually consists of conservative treatment with regular monitoring with ultrasound. In identifying, a thorough evaluation is required. Factors such as sonography characteristics, size and location may help in determining the need for surgery. The origin of gynaecological tumour must be investigated meticulously and malignancy must be ruled out. Explanation must be provided to the patient regarding the risks and benefits of surgery and observations. Early diagnosis and timely intervention is the key to achieve the best possible outcomes for both the mother and the baby.

References

- 1. Sankaranarayanan, R., Ferlay, J. Worldwide burden of gynaecological cancer: the size of the problem. (2006) Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 20(2): 207- 225.

- 2. Dobashi, M., Isonishi, S., Morikawa, A., et al. Ovarian cancer complicated by pregnancy: analysis of 10 cases. (2012) Oncol Lett 3(3): 577– 580

- 3. Kwon, Y.S., Mok, J.E., Lim, K.T., et al. Ovarian cancer during pregnancy: clinical and pregnancy outcome. (2010) J Korean Med Sci 25(2): 230– 234.

- 4. Gasim, T., Al Dakhiel, S.A., Al Ghamdi, A.A., et al. Ovarian tumors associ¬ated with pregnancy: a 20-year experience in a teaching hospital. (2010) Arch Gynecol Obstet 282(5): 529– 533.

- 5. Machado, F., Vegas, C., Leon, J., et al. Ovarian cancer during pregnancy: analysis of 15 cases. (2007) Gynecol Oncol 105(2): 446– 450.

- 6. Ueda, M., Ueki, M. Ovarian tumors associated with pregnancy. (1996) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 55(1): 59– 65.

- 7. Matsuyama, T., Tsukamoto, N., Matsukuma, K., et al. Malignant ovarian tumors associated with pregnancy: report of six cases. (1989) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 28(1): 61– 66.

- 8. Halila, H., Stenman, U.H., Seppala, M. Ovarian cancer antigen CA 125 levels in pelvic inflammatory disease and pregnancy. (1986) Cancer 57(7): 1327– 1329.

- 9. Gezginc, K., Karatayli, R., Yazici, F., et al. Ovarian cancer during pregnancy. (2011) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 115(2): 140– 143.

- 10. Whitecar, M.P., Turner, S., Higby, M.K. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. (1999) Am J Obstet Gynecol 181: 19- 24.

- 11. Modi, M., Nash, K., Mukhopadhaya, N. Ovarian cysts in pregnancy. (2013) RCOG World Congress.

- 12. Hoover, K., Jenkins, T.R. Evaluation and management of adnexal mass in pregnancy. (2011) Am J Obstet Gynecol 205(2): 97- 102.

- 13. Novak, E.R., Woodruff, J.D. Myoma and other benign tumours of the uterus. Novak’s gynecologic and obstetric pathology with clinical and endocrine relations. (1979) Philadelphia: WB Saunders p. 795– 801.

- 14. Ouyang, D.W. Economy, K.E., Norwitz, E.R. Obstetric complications of fibroids. (2006) Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 33(1): 153– 169.

- 15. Sparić, R. Uterine myomas in pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium. (2014) Srp Arh Celok Lek 142(1–2): 118–124.

- 16. Rice, J.P., Kay, H.H., Mahony, B.S. The clinical significance of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. (1989) Am J Obstet Gynecol 160(5 pt 1): 1212– 1216.

- 17. Exacoustos, C., Rosati, P. Ultrasound diagnosis of uterine myomas and complications in pregnancy. (1993) Obstet Gynecol 82(1): 97– 101

- 18. Hasan, F., Arumugam, K., Sivanesaratnam, V. Uterine leiomyomata in pregnancy. (1991) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 34(1): 45– 48.

- 19. Vergani, P., Locatelli, A., Ghidini, A., et al. Large uterine leiomyomata and risk of cesarean delivery. (2007) Obstet Gynecol 109(2 pt 1): 410– 414.

- 20. Coronado, G.D., Marshall, L.M., Schwartz, S.M. Complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery with uterine leiomyomas: a population based study. (2000) Obstet Gynecol 95(5): 764– 769.

- 21. Koo, Y.J., Kim, T.J., Lee, J.E., et al. Risk of torsion and malignancy by adnexal mass size in pregnant women. (2011) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90(4): 358– 361.

- 22. Bottomley, C., Bourne, T. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cyst accidents. (2009) Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 23(5): 711- 724.

- 23. Ko, M.L., Lai, T., Chen S. Laparoscopic management of complicated Adnexal masses in the first trimester of pregnancy. (2009) Fertil Steril 92(1): 283– 287.

- 24. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Ovarian cyst in post-menopausal women. (2003) Greentop Guidelines (34).

- 25. Leiserowitz, G.S., Xing, G., Cress, R., et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? (2006) Gynecol Oncol 101(2): 315- 321.

- 26. Struyk, A.P., Treffers, PE. Ovarian tumors in pregnancy. (1984) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 63(5): 421– 424.

- 27. Whitecar, M.P., Turner, S., Higby, M.K. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. (1999) Am J Obstet Gynecol 181(1): 19– 24.

- 28. Hermans, R.H., Fischer, D.C., van der Putten, H.W., et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy. (2003) Onkologie 26(2): 167–172.

- 29. Bromley, B., Benacerraf, B. Adnexal masses during pregnancy: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis and outcome. (1997) J Ultrasound Med 16: 447–452; quiz 453– 454.

- 30. Ueda, M., Ueki, M. Ovarian tumors associated with pregnancy. (1996) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 55(1): 59– 65.

- 31. Bernhard, L.M., Klebba, P.K., Gray, D.L., et al. Predictors of persistence of adnexal masses in pregnancy. (1999) Obstet Gynecol 93(4): 585– 589.

- 32. Zanetta, G., Mariani, E., Lissoni, A., et al. A prospective study of the role of ultrasound in the management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. (2003) BJOG 110(6): 578– 583.

- 33. Marino T, Craigo SD. Managing adnexal masses in pregnancy. (2000) Contemp Obstet Gynecol 45: 130– 143.

- 34. Schilder, J.M., Thompson, A.M., DePriest, P.D., et al. Outcome of reproductive age women with stage IA or IC invasive epithelial ovarian cancer treated with fertility-sparing therapy. (2002) Gynecol Oncol 87(1): 1– 7.

- 35. Morice, P., Camatte, S., Wicart-Poque, F., et al. Results of conservative management of epithelial malignant and borderline ovarian tumours. (2003) Hum Reprod Update 9(2): 185– 192.

- 36. Kaymak, O., Ustunyurt, E., Okyay, R.E., et al. Myomectomy during Cesarean section. (2005) Int J Gynecol Obstet 89(2): 90– 93.

- 37. Hasan, F., Armugam, K., Sivanesaratnam, V. Uterine leiomyomata in pregnancy. (1990) Int J Gynecol Obstet 34(1): 45– 48.

- 38. Rosati, P., Exacoustos, C., Mancuso, S. Longitudinal evaluation of uterine myoma growth during pregnancy. (1992) J Ultrasound Med 11(10): 511– 515.

- 39. Myerscough PR. Pelvic tumors. Other surgical complications in pregnancy, labor and the puerperium. In: Munro Kerr’s Operative Obstetrics. 10th ed. (1982) London: Bailliere Tindall Publications p. 203– 411.

- 40. Katz, V.L., Dotters, D.J., Droegemueller, W. Complications of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. (1989) Obstet Gynaecol 73(4): 593– 596.

- 41. Roman, A.S., Tabsh, K.M.A. Myomectomy at the time of cesarean delivery: retrospective cohort study. (2004) BMC pregnancy and childbirth 4(1): 14.

- 42. Ortac, F., Gungor, M., Sonmezer, M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. (1999) Int J Gynecol Obstet 67(3): 189–190.

- 43. Sapmaz E, Celik H, Altungul A. Bilateral ascending uterine artery ligation vs. tourniquet use for haemostasis in cesarean myomectomy: a comparison. (2003) J Reprod Med 48: 950– 954.

- 44. Cobellis, L., Florio, P, Stradella, L., Lucia,, E.D., Messalli EM, Petraglia F. Electro-cautery of myomas during cesarean section: two case reports. (2002) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 102(1): 98– 99.

- 45. Hassiakos, D., Christopoulos, R., Vitoratos, N., et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section: a safe procedure? ( 2006) Ann N Y Acad Sci 1092: 408- 13.

- 46. Wallach, E.E. Myomectomy. In: Thompson JD, Rock JA, editors. Te Linde’s operative gynaecology. New York: (1992) JB Lippincott Company p. 647– 62.

- 47. Song, D., Zhang, W., Chames, M.C, Guo J. Myomectomy during cesarean delivery. (2013) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 121(3): 208– 213.

- 48. Burton, C.A., Grimes, D.A,. March, C.M. Surgical management of leiomyoma during pregnancy. (1989) Obstet Gynecol 74(5).

- 49. Li, H., Du, J., Jin, L., et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section. (2009) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 88: 183– 6.

- 50. Hassiakos, D., Christopoulos, R., Vitoratos, N., Myomectomy during cesarean section: a safe procedure? (2006) Ann N Y Acad Sci 1092: 408- 13.

- 51. Yuddandi, N. Gleeson, R., Gillan, J. Management of a massive caseous fibroid at cesarean section. (2004) J Obstet Gynaecol 24(4): 455– 456.

- 52. Roman, A.S., Tabsh, K.M. Myomectomy at time of cesarean delivery: A retrospective cohort study. (2004) BMC Pregnancy Child birth 4: 14- 17.

- 53. Hassiakos, D., Christopoulos, P., Vitoratos, N., et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section: A safe procedure? (2006) Ann NY Acad Sci 1092: 408- 413.

- 54. Pavlidis, N. Coexistence of pregnancy and malignancy. (2002) Oncologist 7: 279- 287.