Mentoring in Occupational therapy and Physiotherapy, its place in a Palliative Medicine multidisciplinary mentoring program

Yap, H.W , Chua, J, Choi, H.J , SAM Mattar , Kanesvaran, R, Radha Krishna, L.K

Affiliation

- 1Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore

- 2Assisi Hospice, Singapore

- 3Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center, Singapore

- 4Nanyang Polytechnic, Singapore

- 5Department of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Center, Singapore

- 6Duke-NUS Postgraduate Medical School, Singapore

- 7Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore

- 8Center for Biomedical Ethics, National University Singapore

Corresponding Author

Toh Ying Pin, Division of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Singapore, 11 Hospital Drive, Singapore 169610, Singapore, Tel: +6564368183; E-mail: ann.typ@gmail.com

Citation

Yap,H.W., et al Thematic Review of Mentoring in Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy between 2000 and 2015, Sitting Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy in A Holistic Palliative Medicine Multidisciplinary Mentoring Program. (2017) J Palliat Care Pain Manage 2(1): 1- 10

Copy rights

© 2017 Yap, H.W. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Mentoring; Physiotherapy; Occupational therapy; Palliative medicine; Multidisciplinary

Abstract

Background: Mentoring develops attitudes and skills in caring for patients at the end-of-life yet it is not formally employed in most Palliative Medicine programs. In part these gaps are the result of a failure to account for mentoring’s context-specific, goal-sensitive, mentee-, mentor- and organizationally-dependent nature that prevent simple adaptations of mentoring practices across sites and a lack of consideration of Palliative Medicine’s multidimensional team (MDT) approach that demands use of a consistent mentoring approaches by the senior members MDT who come from different clinical and healthcare backgrounds. A dearth of mentoring data in physiotherapy and occupational therapy however threatens these plans for a consistent Palliative Medicine mentoring approach.

Aim: Circumnavigating mentoring’s context-specific, goal-sensitive, mentee, mentor and organizationally-dependent nature this thematic review seeks to identify common themes through the identification of common themes within prevailing mentoring practices in physiotherapy and occupational therapy that can be applied in other mentoring settings.

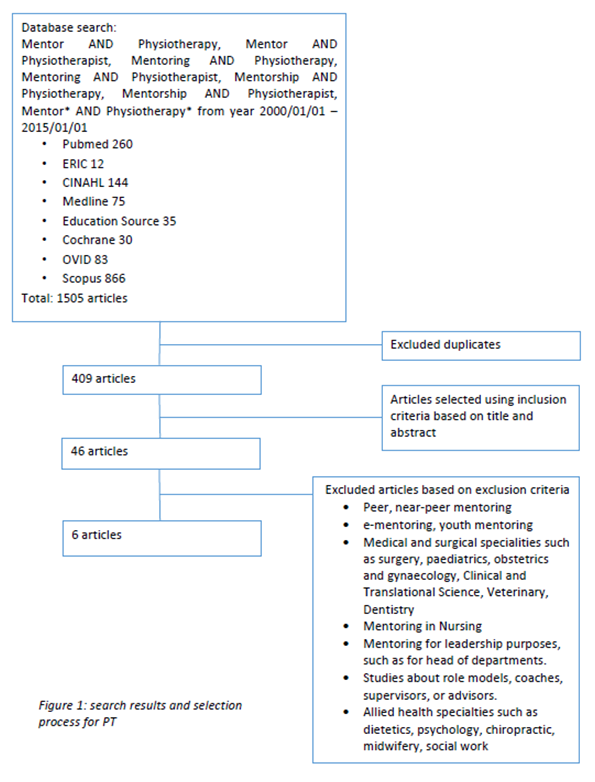

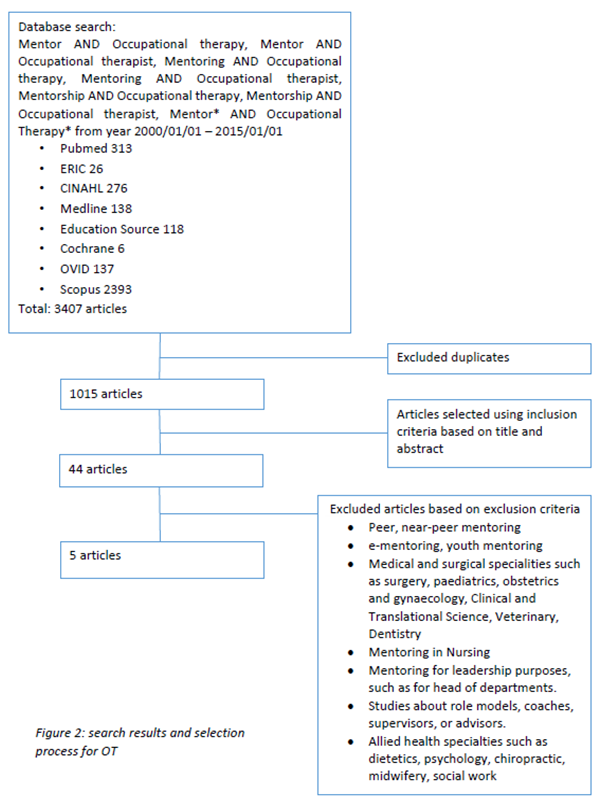

Methodology: Literature search for mentoring programs in physiotherapy and occupational therapy was carried out in PubMed, ERIC, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Medline, Scopus, OVID, CINAHL and Education Source databases from 1st January 2000 to 1st January 2015. Studies of all designs and approaches to mentoring were included. We excluded mentoring for leadership, patient, family, youth, peer and near-peer mentoring, supervision, counseling, advising, coaching, preceptorship, role modeling and sponsorship.

Results: In physiotherapy, 1505 abstracts were retrieved, 46 full-text articles were analyzed and 6 papers were included in this review. In occupational therapy, 3407 abstracts were retrieved, 44 full-text articles were analyzed and 5 papers were included in this review. Separate thematic analysis of physiotherapy and occupational therapy papers revealed 3 common themes which include (1) defining mentoring, (2) benefits of mentoring and (3) mentors and mentees’ perspective about the mentoring process.

Conclusion: Common features within prevailing mentoring programs in physiotherapy and occupational therapy underlines their role within multidisciplinary team mentoring in palliative medicine.

Introduction

Mentoring is seen as an effective means of improving skills, attitudes and practices in caring for dying patients”, providing holistic and personalized support and advancing the academic and research interests amongst trainees that is lacking in Palliative Medicine (PM) training[1-11]. However, the absence of a clear definition and the presence of diverse mentoring practices limits understanding and use of mentoring in PM[8-11].

PM’s use of a multidisciplinary team approach[12] which is “a group of people of different health-care disciplines, which meets together at a given time (whether physically in one place, or by video or tele-conferencing) to discuss a given patient and who are each able to contribute independently to the diagnostic and treatment decisions about the patient” further complicates efforts to introduce mentoring in PM training[12]. Wu., et al’s (2016), Wahab., et al’s (2016) and Loo., et al’s (2017) suggest that use of a MDT mentoring approach in PM which would see senior members from different clinical and healthcare backgrounds within the MDT mentoring PM trainees to ensure a holistic mentoring experience. The presence of various healthcare specialists from diverse clinical settings however makes provision of effective oversight, consistency in mentoring goals, role awareness and clarity in expectations and responsibilities, difficult and underscores the need for a consistent mentoring approach[8-16].

However design of such a holistic and consistent mentoring approach is further complicated by the failure of many reviews and studies to account for mentoring’s context-specific, goal-sensitive, mentee-, mentor- and organizationally-dependent nature which make comparisons between prevailing mentoring practices difficult[8,9,10,11]. To address these concerns Wu., et al (2016), Wahab., et al., (2016), Yeam., et al (2016), Loo., et al (2017) and Toh., et al (2017) have argued that thematic analysis of prevailing mentoring practices could be used to identify common elements that could be applied in diverse settings as guiding principles that will better inform design of mentoring programs. Wu., et al (2016) and Wahab et al (2016) efforts to identify common themes in the mentoring approaches of key members of the MDT however were left frustrated by the lack of systematic, literature and narrative reviews in OT and PT.

The need for this study

This review is aimed at filling the gap in mentoring knowledge in OT and PT. Concurrent evaluation of mentoring programs in OT and PT is justified given that both specialties will be used together in MDT mentoring programs.

Acknowledging the intention to employ senior mentors from the core specialties within the MDT to mentor PM trainees in a consistent and transparent manner within a structured mentoring program, this review will confine itself to mentoring between a senior OT or PT and newly graduated and/or undergraduates from their respective specialties.

Methodology

A thematic review of mentoring programs in OT and PT involving PubMed, ERIC, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Medline, Scopus, OVID, CINAHL and Education Source databases between from 1st January 2000 to 1st January 2015 was conducted to study mentoring programs and approaches used in the PT and OT training. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual Version 2016[17] was used for appraisal of the articles selected refer to Appendix 2. The search terms employed for physiotherapy were: “mentor”, “mentoring”, “mentorship” AND “Physiotherapy*”, “Physiotherapist” or their combinations. The search terms employed for occupational therapy were: “mentor”, “mentoring”, “mentorship” AND “Occupational therapy*”, “Occupational therapist” or their combinations. Publications in English or those with English translations on mentoring programs run by OT or PT departments and/or programs that involved senior PT or OT faculty focused upon advancing the professional and/or personal development of trainees from their respective fields were included.

We included all study designs and mentoring approaches including dyadic (one-to-one, senior-to-junior, face-to-face), group and e-mentoring approaches which entailed combining face-to-face meetings[18] with online, text messaging and/or email[19].

We excluded leadership, patient, family, youth, peer and near-peer mentoring as they are considered distinct forms of mentoring. Practices such as supervision, counseling, advising, coaching, preceptorship, role modeling and sponsorship, which are often conflated with mentoring, were excluded. Supervision is defined as being focused upon professional development, preceptorship as helping students gain clinical competencies, coaching as facilitating learner development through use of “deliberate practice strategies”, role-modelling as creating a positive example of good practice, an advisor as helping with scheduling, logistics and applications and sponsorship as dependence upon the influence of another for promotion and advancement[ 9,10,20,21,22].

These specifications allowed the adoption of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) College of Palliative Care’s (2006) definition of mentoring to facilitate consistent identification of mentoring accounts. The AAHPM definition[6] see mentoring as a “dynamic, reciprocal relationship in a work environment between an advanced career incumbent (mentor) and a beginner (protege), aimed at promoting the development of both”.

In the absence of an a priori framework for mentoring and a lack of understanding of mentoring processes, we carried out a thematic analysis of mentoring programs. Using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach[23], codes were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning of the data and semantic themes were identified from ‘detail rich’ codes.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Two authors (YHW, JC) carried out independent searches and reviews of all full text reviews fulfilling the inclusion criteria. The final list of papers to be included was agreed upon by four authors. The four authors carried out independent thematic analysis of the papers and discussed and compared their results online. Any disagreement in the coding was discussed online and at face-to-face meetings where consensus agreements were achieved.

Results

Search results and Selection process

Figure 1: Search results and selection process for PT .

1505 PT abstracts were retrieved, 46 full-text articles were analyzed and 6 papers[24,25,26,27,28,29] were included in this review.

Figure 2:

3407 abstracts on OT were retrieved, 44 full-text articles were analyzed and 5 papers[30,31,32,33,34] were included in this review.

Separate thematic analysis of PT and OT papers revealed 3 themes including (1) defining mentoring, (2) benefits of mentoring and (3) mentors and mentees’ perspective about the mentoring process.

(1) Defining mentoring

Table 1: Common elements in definitions of mentorship.

| Definition | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Relationship | • Father figure • Guides and develops • Experienced mentors and motivated protégés • Building passion • Keeping fresh • Role model • Bounce ideas off • Non-competitive, nurturing relationship • sharing knowledge and experience |

• More experienced individual works closely with a mentee • Purposes of teaching, guiding, supporting and facilitating professional growth and development • lesser experienced therapist • Stimulating intellectual growth, assisting with research and grant-writing skills • Encouraging problem identification, assisting with publishing and helping to acclimatize to an academic environment |

| Working definition of mentorship | • Promoting deeper learning • Assess their strengths and weaknesses • Help in overall career development • specifically to lead and guide a less experienced person |

• Address career development, where desired • Agreed upon goals of having lesser experienced therapist grow, develop • Deliberately matched and have regular dialogue on a range of issues |

| Reciprocal Relationship | • Relationship focused on sharing knowledge and experience | • Partnership model in which both participants contribute to the relationship |

Thematic analysis of the 4 definitions of mentoring in PT[24,25,26,27] and the 4 definitions of mentoring in OT[30,31,32,33,34] identified common elements. The findings suggest mentoring is a mutually beneficial relationship involving an experienced professional who oversees the professional and personal development of a novice through the sharing of knowledge and skills. All 8 accounts describe mentoring programs supported by organizational assistance and use matching of mentors and mentees[35] to initiate mentoring relationships.

(2) Benefits of mentoring

a. Benefits to mentors

Table 2: Benefits of mentoring for mentors.

| Benefits to Mentor | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Professional benefits | • Opportunity to learn new skills and ideas from mentees • Enhancing their own knowledge and skills in discussion with more recently trained colleagues • Trained and paid for mentoring |

• Catalyst to update their knowledge of current research and its impact on practice • Important influence on abilities to integrate research into their practice • Enhance reputation and professional growth • Keep in touch with current issues that are affecting the practice of occupational therapy • Increased understanding of theory and how theory relates to practice • Positive influence on their research productivity |

| Personal benefits | • Empowerment from helping develop someone else’s career • Refreshing to see different way of thinking • Important mechanism for motivating them to keep upto- date with research and advance their clinical skills • Renewed desire to learn • Stimulating reflection on their own clinical practice • Continually challenging their own practice |

• Gratification stimulation • A feeling of giving back to future professionals |

The professional and personal benefits of mentoring for mentors feature in 3 articles in PT[25,27,29] and 5 in OT[30,31,32,33,34,35] (Table 2). The professional benefits include refreshing and updating skills and knowledge, remaining up-to-date, increasing research productivity and enhancing professional reputation[25,27,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Common personal benefits include formal acknowledgement of the mentor’s work and being able to ‘pay it forward’[25,27,29,30,31,32,33,34].

b. Benefits to mentees

5 articles in PT[24,25,26,27,29] and 4 accounts in OT[30,31,32,33,34] report on the benefits of mentoring for mentees (Table 3). Common professional benefits include gaining practical experience, benefiting from a safe platform for discussion and feedback, developing research, clinical and decision making skills and professional identity and faster promotions[25,27,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Common personal benefits include improved self-confidence and personal development[25,27,29,30,31,32,33,34].

c. Benefits to host organizations

Table 3: Benefits of mentoring for mentees.

| Benefits to mentee | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Professional benefits | • Able to handle new and complex clinical situations • Provides experiences for novice practitioners to expedite their learning and engage in reflection-on-action by working with their mentors • Develop clinical decision-making skills • Assist IEPs in preparation for taking IEP exams • Assisting with problem solving around a difficult patient • Help in professional issues or managing a clinical practice • Provided direction around continuing education courses and career paths • Provided feedback in the form of recognition and support for career goal setting • Promoted improved patient outcomes by providing a forum for clinical decision making • Making career choices to achieve success • Empowered to foster growth and success of the individual’s professional identity |

• Provided a forum to find resources, guidance and support • Provided insight into Occupational therapy practice • Positive role model reinforcing professionalism • Good for job information and portfolios • Develop professionalism • Instilling greater professional expertise and commitment to one’s profession Faster rate of promotion for mentees Increasing the research productivity of junior faculty mentees Opportunity to reflect on practice in a honest, safe and professional environment Develop skills in applying theory to real clinical situations • Widen and challenged perspective of clinical work • Facilitated personal and professional growth • Improve academic adjustment and performance • Improve one’s teaching and research skills • More productive with publications, presentations and grantsmanship • Keep pace with the demands and requirements of academia • Provided an opportunity to obtain a formal mentor to help them succeed in research, teaching and service goals |

| Personal benefits | • Made them aware of the gap between knowledge they acquired at university and that required to effectively interact with patients, carers and service users • Increased self-confidence, self-esteem and independent thinking • Providing encouragement that the new graduates were “on the right track” | • Calmed fears and uncertainties • Validating experiences and struggles • Contributing to a greater job satisfaction • Helped to build confidence • Experience helped develop communication and group skills |

Table 4: Benefits of mentoring for stake holders.

| Benefits to stakeholders | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| • Integral to students’ development as future healthcare professionals, and its implementation might be of relevance to current and future educators • Increased passing rate of IEPs taking the PCE has been achieved with international graduates who took the program • Continuing education program could focus on promoting patient success through enhancing skill in sound and autonomous decision making rather than focusing on credentials, whereas personal support likely promotes professional success through guiding goal setting and career choices that will foster success |

• Established formal mentoring programs to assist individuals in their development and advancement • Offered mentoring programs because it has been linked with reduced employee turnover and increased roductivity • Mentoring can be used as a recruitment tool by departments and universities • Joint publications, presentations and grants by junior and senior faculty • Academic achievements and productivity of individual occupational therapy faculty members can contribute to the success and recognition of the profession in the university community and society |

Common benefits to the host organizations include better trained staff[29,31] and accelerated professional progression amongst staff[27,31,34].

(3) The mentoring process

a. Mentor’s perspective

Mentors emphasized the need for appropriate mentoring styles and compatible interests with mentees[25,29,34]. In addition mentors stressed the importance of ‘protected time’[25,29,32,33,34] to ensure an effective mentoring experience and to nurture reflective and critical thinking[25,29,32,33,34].

Table 5: Mentor’s perspective of the mentoring process.

| Mentor’s perspective | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Areas of weakness | • Few IEPs utilised the allocated time with mentors | • Personality conflicts in the group • felt expectations were not clear • more outcome evaluation was needed • the pass/fail marking did not motivate the mentees • they experienced difficulty when there was a lack of connection between mentor and mentee • lack of time • mentors thought that they had had a limited connection with their mentees |

| Thoughts on mentoring | • Pave the way for a quality experience • Knowledge translation focuses on promoting mentee’s ability to transfer academic learning into clinical situations • Mentoring stimulates reflecting thinking • Mentoring is a critical tool for advancing patient care • Identifying compatible learning style assists the mentor and mentee in this process of knowledge translation |

• Enhances their own learning and challenged them to explicate and defend their own practice theories • Providing opportunities for modelling research retrieval and discussing application to practice • Found their group to be great, bright, eager and responsible • Rewarding to watch the student develop • Reciprocal learning took place • Challenging but refreshing to hear students perspective • Good opportunity to lend insight and support • Provided connection to the curriculum and the university • Different from teaching or being a supervisor • It’s an important need in student development • Valuable support in the transition from student to clinician • Connected students to the profession early In the long term, needs continue to be met by the relationship and thus they continue the relationship past the program |

b. Mentee’s perspective

Table 6: Mentees’ perspective of the mentoring process.

| Perspectives of mentees | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Area of weaknesses | • IEPs found other components of the program of more benefit, such as practice exams, workshops, clinical lab days | • However, many mentees were uncertain because they felt the mentor– mentee connection was too contrived, short term, or they did not feel connected to their mentor. • Mentees also stated that continuing the relationship would depend on the city in which they would live after graduation • a lack of connection with their mentor including difficulty relating • feeling that the relationship was too contrived, having expectations not met • a sense that the mentor’s clinical area was different from where the mentee intended to practice |

| • Mentors practices the way I want to practice • They help guide my skills, to develop me skills, so that I can practice in a similar fashion • They also pull out things that are your strengths and help you to develop those as well • Allowed me to feel less intimidated by new situations • Provided someone with whom to discuss other issues relating to our profession • Influenced their career decisions throughout their career, including their decisions to enter the profession • Mentorship and self-reflection has the greatest impact on the career choices they made |

• Many found the mentorship program to be a positive, inspiring or valuable experience • Mentees found that mentors were helpful, open, flexible, useful, supportive partners, and contributed interesting ideas to the group • Mentees found the mentor group to be a supportive environment for discussions, where ideas can be expressed and questions asked freely • Mentorship program facilitated professionalism, provoked thinking, or was a good learning experience • The program provided insight into real occupational therapy and the relationship with the mentor developed over time • Mentors were open, enthusiastic, allowed students to run the group, great facilitator, genuine interest, understood and valued mentee role, patient, understanding, a more experienced peer in the group, listened, assisted if she could, warm, friendly, respectful, professional, leader, available, encouraged independent thinking, role model, can related to mentee, calms mentee fear, and see other perspectives • Mentee found that her needs continued to be met be the relationship and that both mentee and mentor are still learning through their relationship after the program • Mentee and mentor continued the relationship even after the program |

Mentoring was most effective when mentees and mentors were well matched sharing the same interests and goals and when mentees provided with career advice[24,27,29,30,32,33]. Mentees also appreciated consistent mentoring experiences, effective role modeling and supportive environments that allowed frank discussions, effective feedback, clinical insights and facilitated reflective practice[24,27,29,30,32,33]. Good mentoring interactions led to prolonged ties long after the mentoring project ceased[27,29,30,34].

Discussion

We will discuss the common theme in PT and OT mentoring programs in turn.

Relational-Dependent nature

OT and PT mentoring relationships pivot on effective matching of mentees and mentors with similar goals and interests. Mismatches result in a reduction of interest amongst mentees and discourage their investment of time and effort in the mentoring process. As a result, pre-mentoring meetings hosted by host organizations where goals, time lines, responsibilities and code of conduct are established are important. Such meetings prevent misunderstandings and set the tone of the mentoring process. They also help nurture personal ties and lasting friendships.

Organizational-Dependent nature

Host organizations play significant roles within mentoring relationships. Practically host organizations provide ‘protected time’ that allow mentors time set aside to provide effective, timely, appropriate, and individualized support. A critical role of the host organization involves nurturing mentoring environments that facilitate frank discussions and conversations about personal matters. Host organizations also provide mentor training and guidance for mentees. This is pivotal to establishing personal ties in mentoring relationships. In addition, host organizations provide formal recognition of mentoring efforts.

Host organizations also play key relational roles facilitating the matching process, providing additional personal and professional support for mentees and mentors and providing oversight of the mentoring process.

Mentee-dependent nature

A mentee’s character, motivations to participate, willingness to invest in a mentoring relationship and ability to realize mentoring objectives are critical. These mentee-dependent features are intimately entwined with the ability of the mentor to relate, inspire, work and support them.

Mentor-dependent nature

The mentoring relationship is dependent upon the ability of the mentor to adopt the appropriate mentoring approach, nurture trusting relationships and provide effective, appropriate, timely, specific and individualized feedback.

Evolving nature of mentoring

The various roles of the mentor at different stages of the mentoring relationships and the presence of short and medium term objectives within the mentoring process hint at mentoring’s evolving nature. The evolving nature of mentoring is emphasized by relationships that extend beyond the program and change into friendship over years[36,37,38].

Overall mentoring in PT and OT reveal evolving, mentee, mentor, organizational and relational dependent features akin to mentoring in medicine, surgery and nursing[8,9,10,11]. These similarities suggest consistency in the mentoring approaches of the key specialties in the MDM and would suggest that senior OTs and PTs could be part of a consistent MDT mentoring process in PM.

Limitations & further research

Whilst data does point to similarities between mentoring in OT and PT and the other specialties in the MDM, gaps remain. Lacking is data on context-specificity or goal-sensitivity that were pivotal to mentoring in medicine, nursing and surgery. Furthermore, what little evidence existing is largely American and may not be easily adaptable to other mentoring settings.

Conclusion

Consistent, timely, holistic and individualized support that cuts across specialties provided by senior members of the MDT in a structured program that will provide transparency and accessibility to mentoring in PM is long overdue. This is particularly evident in the knowledge that PM can no longer afford to train its trainees along specialty lines. This review suggests that inclusion of OT and PT into a MDT mentoring program is possible but does raise questions as to how best to approach the design of a consistent mentoring approach.

It may be that looking for commonalities in the mentoring approaches of core MDT specialties to design a mentoring approach that can be used by all MDT mentors is flawed. One alternative maybe that a consistent form of MDT mentoring based upon the common themes identified within nursing, OT, PT, MSW and medicine mentoring approaches could be applied amongst MDT specialties. Further research on both these option is required as is research of mentoring within the PM setting.

Acknowledge:

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S. Radha Krishna and Dr Deborah Watkinson whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix 2

Appendix 2: JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research.

| Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 2 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 3 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 4 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 5 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 6 | Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 7 | Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 8 | Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 9 | Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 10 | Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

Appendix 2: Results of Critical Appraisal for Selected Qualitative Papers.

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ezzat A 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Solomon P 2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes |

| Takeuchi R 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Craik J 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | Yes |

Appendix 2: JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies.

| Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 2 | Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 3 | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 4 | Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 5 | Were confounding factors identified? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 6 | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 7 | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 8 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

Appendix 2: Results of Critical Appraisal for Selected Analytical Cross Sectional Studies paper.

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solomon P 2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Thomson D 2011 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | NA | NA |

| Greig A 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Milner T 2005 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Paul S 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Milner T 2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes |

Appendix 2: Results of Critical Appraisal for Randomized Controlled Trials paper.

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williams A 2014 | NA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||

| Williams A 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Appendix 2: JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials.

| Yes | No | Unclear | NA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 2 | Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 3 | Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 4 | Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 5 | Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 6 | Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 7 | Were treatments groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 8 | Was follow-up complete, and if not, were strategies to address incomplete follow- up utilized? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 9 | Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomized? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 10 | Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 11 | Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 12 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| 13 | Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

References

- 1. Carey, E., Weissman, D. Understanding and Finding Mentorship: A Review for Junior Faculty. (2010) J Palliat Med 13(11): 1373-1379.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 2. Jackson, V., Arnold, R. A Model of Mosaic Mentoring. (2010) J Palliat Med 13(11): 1371-1371.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 3. Arnold, R. Mentoring the Next Generation: A Critical Task for Palliative Medicine. (2005) J Palliat Med 8(4): 696-698.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 4. Case, A., Orrange, S., Weissman, D. Palliative Medicine Physician Education in the United States: A Historical Review. (2013) J Palliat Med 16(3): 230-236.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 5. Periyakoil, V. Declaration of Interdependence: The Need Mentoring in Palliative for Mosaic Care. (2007) J Palliat Med 10(5): 1048-1049.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 6. Kutner, J. AAHPM College of Palliative Care: Mentorship and Career Development. (2006) J Palliat Med 9(5): 1037-1040.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 7. Sullivan, A., Lakoma, M., Block, S. The status of medical education in end-of-life care. (2003) J General Internal Medicine 18(9): 685-695.

Pubmed || Crossref|| Others - 8. Yeam, C.T., Kanesvaran, R., Krishna, L.K.R., et al. An Evidence-Based Evaluation of Prevailing Learning Theories on Mentoring in Palliative Medicine. (2016) Palliat Med Care 3(1): 1-7.

Others - 9. Wu, J.T., Wahab, M., Loo, W., et al. Toward an Interprofessional Mentoring Program in Palliative Care - A Review of Undergraduate and Postgraduate Mentoring in Medicine, Nursing, Surgery and Social Work. (2016) J Palliat Care Med 06(06).

Others - 10. Wahab, M., Wu, J.T., Ikbal, M.F.M., et al. Creating Effective Interprofessional Mentoring Relationships in Palliative Care- Lessons from Medicine, Nursing, Surgery and Social Work. (2016) J Palliat Care Med 06(06).

Others - 11. Loo, T., Mohamad Ikbal, M., Wu, J.T., et al. Towards a Practice Guided Evidence Based Theory of Mentoring in Palliative Care. (2017) J Palliat Care Med 7: 296.

Others - 12. Zaw, O., Muang, A., Wei, S., et al. The role of the multidisciplinary team in decision making at the end of life. (2015) Advances in Medical Ethics.

<Others - 13. Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, University of Michigan. (2004) Health Education & Behavior 31(6): 835-835.

Crossref - 14. Fleissig, A., Jenkins, V., Catt, S., et al. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK?. (2006) Lancet Oncol 7(11): 935-943.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 15. Acute Oncology Measures. 1st ed. National Cancer Peer Review-National Cancer Action Team; 2011.

- 16. Kashiwagi, D., Varkey, P., Cook, D. Mentoring Programs for Physicians in Academic Medicine: a systematic review. (2013) Acad Med 88(7): 1029-1037.

Pubmed || Crossref - 17. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual. 2016 edition. (2016) Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute.

Others - 18. Notess, M., Plaskoff, J. Preliminary heuristics for the design and evaluation of online communities of practice systems. (2002) eLearn 2002(12): 5.

Crossref || Others - 19. Griffiths, M. E-mentoring: Does it have a place in medicine?. (2005) Postgrad Med J 81(956): 389-390.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 20. Witry, M., Patterson, B., Sorofman, B. A qualitative investigation of protégé expectations and proposition of an evaluation model for formal mentoring in pharmacy education. (2013) Res Social Admin Pharm 9(6): 654-665.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 21. Gifford, K., Fall, L. Doctor Coach. (2014) Academic Medicine 89(2): 272-276.

Crossref - 22. Travis, E., Doty, L., Helitzer, D. Sponsorship. (2013) Academic Medicine 88(10): 1414-1417.

Crossref - 23. Braun, V., Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. (2006) Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101.

Crossref || Others - 24. Solomon, P., Ohman, A., Miller, P. Follow-up Study of Career Choice and Professional Socialization of Physiotherapists. (2004) Physiother Can 56(02): 102.

Crossref - 25. Ezzat, A., Maly, M. Building Passion Develops Meaningful Mentoring Relationships among Canadian Physiotherapists. (2012) Physiother Can 64(1): 77-85.

Pubmed || Crossref - 26. Thomson, D., Hilton, R. An evaluation of students' perceptions of a college-based programme that involves patients, carers and service users in physiotherapy education. (2012) Physiother Res Int 17(1): 36-47.

Pubmed || Crossref - 27. Takeuchi, R., O'Brien, M., Ormond, K., et al. “Moving Forward”: Success from a Physiotherapist's Point of View. (2008) Physiother Can 60(1): 19-29.

Pubmed || Crossref - 28. Williams, A., Phillips, C., Watkins, A., et al. The effect of work-based mentoring on patient outcome in musculoskeletal physiotherapy: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. (2014) Trials 15(1): 409.

Pubmed || Crossref - 29. Greig, A., Dawes, D., Murphy, S., et al. Program evaluation of a model to integrate internationally educated health professionals into clinical practice. (2013) BMC Med Edu 13(1): 140.

Pubmed || Crossref - 30. Wilding, C., Marais-Strydom, E., Teo, N. MentorLink: Empowering occupational therapists through mentoring. (2003) Aust Occup Ther J 50(4): 259-261.

Crossref || Others - 31. Paul, S., Stein, F., Ottenbacher, K., et al. The role of mentoring on research productivity among occupational therapy faculty. (2002) Occup Ther Int 9(1): 24-40.

Pubmed || Crossref - 32. Craik, J., Rappolt, S. Enhancing Research Utilization Capacity through Multifaceted Professional Development. (2006) J OccupTher 60(2): 155-164.

Pubmed || Crossref - 33. Milner, T., Bossers, A. Evaluation of the mentor–mentee relationship in an occupational therapy mentorship programme. (2004) Occupational Therapy International 11(2): 96-111.

Crossref - 34. Milner, T. Evaluation of an Occupational Therapy Mentorship Program. (2005) Can J Occup Ther 72(4): 205-211.

Pubmed || Others - 35. Ragins, B., Cotton, J. Mentor functions and outcomes: A comparison of men and women in formal and informal mentoring relationships. (1999) J Appl Psychol 84(4): 529-550.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 36. Allen, L. Teacher’s Pedagogical Beliefs and the Standards for Foreign Language Learning. (2002) Foreign Language Annals 35(5): 518-529.

Crossref || Others - 37. Johnson, D. Social Interdependence: Interrelationships among Theory, Research, and Practice. (2003) Am Psychol 58(11): 934-945.

Pubmed || Crossref || Others - 38. 38. Marks, M., Goldstein, R. The mentoring triad: mentee, mentor, and environment. (2005) J Rheumatol 32(2): 216-218.

Pubmed || Others