Percutaneous Retrieval of Fractured Catheters from Pediatric Endovascular Tree: Case Series & Literature Review

Mohammed Hussein Habib1*, Mohammed Hillis2, Khaled Hani Alkhodari3

Affiliation

1 Department of Head cardiology and cardiac catheterization, Ph.D. Cardiology, Al-Shifa Hospital, Palestine

2 Pediatric Cardiology Department, Ph.D., Alshifa Hospital, Gaza, Palestine

3The Islamic University of Gaza, MD, Palestine

Corresponding Author

Mohammed Hussein Habib, Department of Head cardiology and cardiac catheterization, Ph.D. Cardiology, Al-Shifa Hospital, Palestine, Email: cardiomohammad@yahoo.com

Citation

Habib, M.H., et al. (2019) Percutaneous Retrieval of Fractured Catheters from Pediatric Endovascular Tree: Case Series and Literature Review J Heart Cardiol 4(1): 8-11.

Copy rights

© 2019 Habib, M.H. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Fractured catheter; Port-a-cath; Embolization to heart

Abstract

Central venous accesses are commonly used in pediatrics for many reasons. There is more than oneway to gain access e.g. port-a-cath, umbilical venous catheter, femoral venous catheter, etc. Each way has its own indications and contraindications. Although they are more beneficial to gain wider access it has more complications that are serious compared with the peripheral access, among them is the fracture of the catheter and migration of it to the heart or lung. Here we present four cases with an embolized catheter in different places in the pediatric vascular tree.

Introduction

Central Venous Access is a commonly used procedure for many indications like in adequate peripheral venous access, cancer chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, Hemodialysis, and others. That access can be gained by many ways like the umbilical vein catheter (UC), Port-A-Cath (PC), or others, which can be, inserted in different veins, like the internal jugular, subclavian, umbilical veins, each one has its own characteristics, and indications. The insertion and removal of CVA should be carried out carefully, to prevent complications, like the embolization of the catheter to the heart or pulmonary artery which is so challenging[1].

Here we report four cases of broken catheters in pediatrics vascular tree; each case is different from the other and has its own challenges.

Case 1

An 8-year old child has polycystic kidney disease, suffering from end-stage renal disease, was placed on Hemodialysis using a PC device for 2 years. The device was first inserted in the two femoral veins and then inserted into the right subclavian vein for about one year. The child started to have general malaise, fever, and pus discharge from the device site for three weeks; as a result, he was admitted into the hospital for 15 days and treated by antibiotics without improvement, so a decision was made to remove the device. The child is then referred to the vascular surgery department, and the removal procedure, unfortunately, is complicated by catheter cut and slippage into his venous tree.

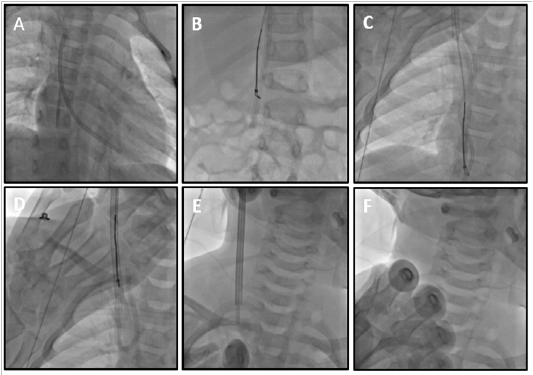

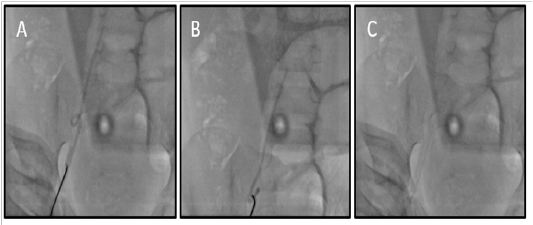

The child then was referred urgently to our heart catheterization center, under fluoroscopy; the PC catheter was lodged in the right ventricle (RV) (Figure 1A). After gaining an informed consent from the patient’s parents; the decision was to sedate the child and remove the wire using 14 fr femoral sheath inserted into his right femoral vein; and unfortunately, that was so difficult, so a trial to use the left femoral vein also failed, finally a trial to use the right internal jugular vein was not easy because there was a narrow space to insert our 14 fr sheath in the presence of central line and the upper tip of the fractured catheter (FC), we took the risk and it succeeded. The patient’s three venous accesses were fibrosed and it was a challenge to insert our sheath. After that, a 6 Fr pigtail catheter was introduced to change the position of the FC from the RV to the Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) was done successfully (Figure 1B), followed by 6 fr snare catheter to catch the FC and they all (the FC, snare catheter, and the sheath) were removed from the child’s heart (Figure 1E). On follow up, there were no complications followed the procedure.

Total procedural time was 60 minutes, with 42 minutes of fluoroscopy. Control fluoroscopy demonstrated total removal of the broken PC FC. Blood loss during the procedure was minimal.

Figure 1: AP view under fluoroscopy showing (A) the fractured PC catheter in the right ventricle, (B, C, D) after changing the FC position into the IVC, a snare catheter was used to catch it and retrieve it from the venous tree through the right internal jugular vein, (F) this view shows total removal of the snare catheter with the FC and the central line.

Case II

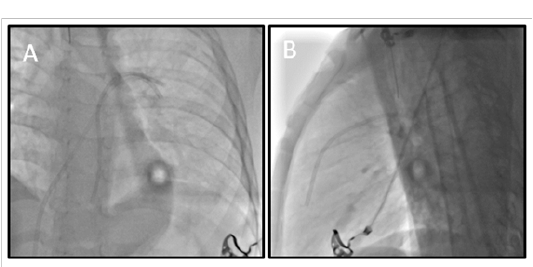

A 5-year old child has-been treated by chemotherapy administered via a PC device, referred to the pediatric surgery department to remove the device; on removal, its catheter slid into the venous tree. The child was urgently referred to our heart catheterization center; under fluoroscopy, the FC was lodged in the left pulmonary artery (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A- an AP view, B- lateral view showing the FC lodged in the left pulmonary artery, and the right ventricle

After gaining an informed consent from the patient’s parents; general anesthesia was performed, andleft femoral vein accesswas achieved using 10 fr sheath, and a 6 fr snare was introduced; a trial to catch the FC was failed many times, so another trial of 6 fr pigtail catheter was successful to get the FC out the heart into the IVC, from there, it wascaught using the snare (Figure 3) and the procedurewas finished without complications.

Total procedural time was 120 minutes, with 40 minutes of fluoroscopy. Control fluoroscopy demonstrated total removal of the broken FC (Figure 3C). Blood loss during the procedure was minimal.

Figure 3: The FC was displaced into the IVC and was cached using the snare catheter and get out the body through left femoral access.

Case III

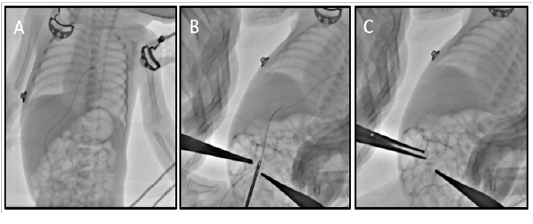

A 28-day old newborn had neonatalsepsis.Central venous access requested;and it was difficult to obtain, so CVAthroughthe right femoral vein was attempted, and complicated by the fracture of the catheter and its retrieval was difficultin bedside, and the vascular surgeon could not remove it with local exploration. Following that, the newborn was referred urgently to our heart catheterization center.

On arrival fluoroscopy was done urgently showed the catheter lodged in the IVC.

Figure 4: Fluoroscopy shows the fractured catheter lodged in the IVC.

After gaining informed consent from the patient’s parents, general anesthesia was done. Our management plan was to use a surgical forcepsfrom the ENT department, after using a 6 fr right femoral sheath, the forceps was introduced (Figure 5A) and many trials was done to catch the catheter but it can not be pulled out, so a decision to use a 6 fr balloon catheter (Figure 5B) was complicated byembolization of the FC into the right ventricle (Figure 5C,D), after that a 6 fr snare catheter was used to catch the catheter and it was successful (Figure 5E, F), the procedure was finished without complications.

Total procedural time was 120 minutes, with 35 minutes of fluoroscopy. Control fluoroscopy demonstrated total removal of the broken FC (Figure 5F). Blood loss during the procedure was minimal.

Figure 5: The sequence of events in the retrieval of a fractured CVA catheter in the IVC: A, ENT Forceps was used to catch the FC; B,C,D,FC embolization to the heart after balloon inflation; E, the use of snare catheter to catch the FC; F, a view shows total removal of the FC from the child vascular tree.

Case IV

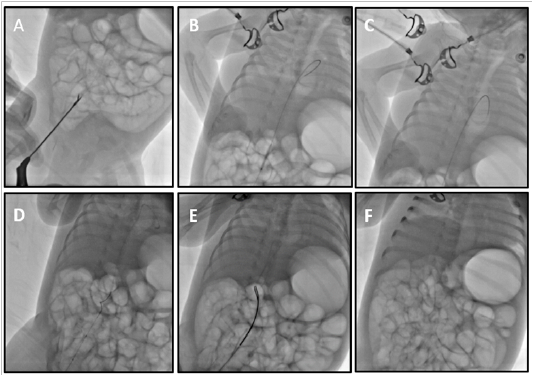

A 28-week-old preterm infant with a birth weight of 1370 g was born by cesarean section. He was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit because of respiratory distress due to meconium aspiration syndrome. He was incubated, mechanically ventilated; A 3.5 Fr UVC was used during initial days of his stay for parenteral nutritional support. After hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization, the UVC was removed on the fourth day of life, but during catheter removal, the UVC got divided by a scalpel at the skin level while removing the retaining suture. An attempt to retrieve the fractured portion of UVC was planned by a local exploration but the end had retracted into the lumen of the umbilical vein and it was not visible. During manipulation, the catheter got accidentally transected and embolized into the left atrium with its one end still remaining in the inferior vena cava (IVC) (Figure 6 A).

The patient was transferred urgently to cardiac catheterization for removal fractured segment by percutaneous technique. Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents. Under general anesthesia, trans-umbilical vein access was done. Intravenous heparin (100 IU / kg) was administered. Cut down of the Umbilical vein was done, then 0.018-in floppy guide wire was cross and advanced into an umbilical vein (Figure 6 B), and the floppy guide wire was exchanged with a five French venous sheath. The fractured fragment of UVC was retrieved with fluoroscopically guided, Though we could hold the catheter very well with the snare, its snared end was making a loop and could not be retrieved back into the 5 F sheath, then small size grasping forceps was cross and catch the distal edge of fractured segment and removal without complications.

Total procedural time was 35 minutes, with 4 minutes of fluoroscopy. Control fluoroscopy demonstrated the total removal of the broken UVC (Figure 6 C). Blood loss during the procedure was minimal.

Figure 6: A, Broken UVC migration via patent foramen oval to left atrial appendage. B, 0.018-in floppy guide wire was cross and advanced into umbilical vein. C, Control fluoroscopy demonstrated total removal of the broken UVC

Discussion

Central Venous Access (CVA) is widely used for many indications like inadequate peripheral venous access, cancer chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, Hemodialysis, and other indications. In addition to that, CVA can be inserted in many veins, e.g. internal jugular, subclavian, umbilical veins; and each one site has its characteristics[1].

Here we report four challenging cases resulted as complications after device removal and were urgently referred to our center. Managing those cases was challenging as the poor publications about those cases and insufficient training regarding the management of such cases. Despite that, we were able to successfully treat those cases in a successful, professional manner, without complications, and without the need foropen surgeries. One of our cases, was difficult, as it was impossible to catch the FC with the snare even after multiple attempts because the small size of pulmonary artery and the friable trabeculae of the right ventricle that should be kept safe to prevent pulmonary valve disease; as a result, transposition of the FC from the heart or the pulmonary artery to the IVC, using pig-tail catheter, could ease the process of FC catching by the snare catheter in the more dilated IVC and retrieve it out the body.

According to Surov et al. 2009, catheter embolization is not common, as the estimated rate ranges from 0.2% to 4.2%; it occurs most commonly as a result of catheter pinch-off syndrome. The most common site for embolization is the pulmonary artery (35%) and most of them are long enough to be in more than one place, especially the pulmonary artery and the right ventricle. Most of the catheters were removed by percutaneous, minimally invasive procedures by an interventional radiologist or a cardiologist[2].

Moreover, after an exhaustive literature review, we found a similar case published by Al-Pakra and Ehab 2015 reporting a PC wire migration to the heart after trauma to the site of insertion[3]. Burzotta et al. 2008, reported a case of 30 years old female with embolized PC wire, and they retrieved it using a home-made coaxial recovery technique, similar to snare catheter[4].

The insertion and removal of CVA should be done carefully, to prevent complications; among the most common is catheter malposition, pneumothorax, hemorrhage, and catheter embolization. Long-term complications include infections, thrombosis, extravasations, catheter disconnection and embolization to the heart or pulmonary artery[5] to prevent that, safe removal techniques should be followed[6].

Although endovascular procedures are relatively safe, and their applications are increasing steadily, its complications are emerging, one of the challenging complications is embolization of parts of the used tools; their retrieval requires well-trained, qualified personnel, who can do that surgically or better percutaneously[7].

References

- 1. Galloway, S., Bodenham, A. Long‐term central venous access. (2004) Br J Anaesth 92(5): 722-734.

- 2. Surov, A., Wienke, A., Stoevesandt, D., et al. Intravascular Embolization of Venous Catheter--Causes, Clinical Signs, and Management: A Systematic Review. (2009) J Parenter Enternal Nutr 33(6): 677-685.

- 3. Al-Pakra, M., Ehab, H. Migration of A Port-A-Cath in to the Heart. (2015) J Cardiol Curr Res 3(4): 1-5.

- 4. Burzotta, F., Romagnoli, E., Trani, C. Percutaneous removal of an embolized port catheter: description of a new coaxial recovery technique including a case-report. (2008) Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 72(2): 289-293.

- 5. Yildizeli, B., Lacin, T., Yuksel, M., et al. Complications and management of long-term central venous access catheters and ports. (2004) J Vasc Access 5(4): 174-178.

- 6. Galloway, S., Bodenham, A. Safe removal of long-term cuffed Hickman-type catheters. (2003) Hosp Med 64(1): 20-23.

- 7. Woodhouse, J.B., Uberoi, R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. (2013) Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 36(4): 888-897.