Prescription pattern of Anti-malarial drugs in Gimbi General Hospital, Western Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study

Firomsa Bekele1*, Dinka Dugassa2, Kumera Bekele3, Sanbato Tamiru4 Tigist Teklu5

Affiliation

1Department of Pharmacy, College of Health Science, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

2Nekemte referral hospital, Nekemte, Ethiopia

3Department of Nursing, College of Health Science, SelaleUniversity, Fiche, Ethiopia

4Department of nursing, College of Health Science, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

5Department of nursing, College of Health Science, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

Corresponding Author

Firomsa Bekele, Department of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia, Tel: +251(0)919536460; E-mail: firomsabekele21@gmail.com

Citation

Bekele, F., et al. Prescription Pattern of Anti-Malarial Drugs in Gimbi General Hospital, Western Ethiopia: Cross-Sectional Study (2019) J pharma pharmaceutics 6(2): 59-64.

Copy rights

© 2019 Bekele, F. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Prescription pattern; Anti- malarial drugs; Malaria; Gimbi

Abstract

Background: Malaria is life threatening blood disease transmitted via the bite of a female Anopheles species of mosquito. Important components for reducing the burden of malaria morbidity and mortality include more sensitive diagnostic tools, effective use of anti- malarial drugs, improved personal and community protection and mosquito control. The intensive prescribing of the drugs available for malaria treatment may result in the development of resistance. The study was to assess the prescription pattern of anti-malarial drugs in Gimbi general hospital.

Method: Retrospective cross-sectional study design was conducted to determine the prescription pattern of anti-malaria drugs in Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018. The data was entered into EPI-manager 4.0.2 software and analysed by using SPSS V.24.

Result: From the total of 384 patients card assessed, 180(46.9%) were female and 204(53.1%) were male. The most commonly prescribed anti-malarial drugs were Coartem 290(66.2%) followed by Chloroquine 91(20.8%), Primaquine 43(9.8%) and Artesunate 14(3.2%). From the total of anti-malarial drugs prescribed, Coartem 288(65.7%) was the most commonly prescribed by brand name and Chloroquine 91(20.8%) was most commonly prescribed by generic names. About 75.5%, 78.4% and 79.2% of anti-malarial drugs were prescribed with appropriate dose, frequency and duration respectively.

Conclusion: Coartem was the most commonly prescribed antimalarial drugs followed by chloroquine, primaquine and artesunate respectively. From the total card reviewed three-fourth of them was prescribed with appropriate dose and the remaining one-fourth was inappropriately prescribed (under dose and over dose). Therefore Presence of clinical pharmacist plays pivotal role in order to facilitate and promote appropriate use of drugs by intervening different problems in prescribing, dispensing and providing necessary advices for the patients and health professionals.

Introduction

Malaria is life threatening blood disease caused by a five Plasmodium species including P.falciparum, P.vivax, P.ovale, P.malariae and more recently P.knowlesi. It is a preventable and treatable disease. If malaria is diagnosed and treated early on, the duration of the infection can be considerably reduced, which in turn lowers the risk of complications and death[1-6].

Different types of anti-malarial drugs used for treatment of malaria includes: Chloroquine, Quinine sulfate, Hydroxychloroquine, Mefloquine, Coartem, Artesunate, quinidine and Primaquine. The types of drugs and the length of treatment will vary, depending on: Which type of malaria parasite, the severity of symptoms and age of patients[7].

The proper control of malaria infection globally is being threatened on an unprecedented scale by rapidly growing resistance of plasmodium falciparum to conventional monotherapy such as chloroquine, sulphadoxine, pyrimethamine and amodiaquine. As a response to the anti-malarial drug resistance situation, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that treatment policies for P.falciparum malaria in all countries experiencing resistance to monotherapy should be on combination therapies, preferably those containing an arteminisin derivative (ACT-arteminisin-based combination therapy)[8].

Prescription practices have been shown to influence the emergence of resistance to anti- malarial drugs. To prevent the emergence of resistant malaria parasites, drug use patterns can be evaluated in terms of prescribing and dispensing practices as well as patients’ use of the drug[9].

The correct use of anti-malarial drug is the key not only to therapeutic success but also to determining the spread of drug resistance to malaria. Informal use of anti-malarial could increase the risk of under-dosage, over dosage or incorrect dosing, treatment failure, the resistance to anti- malarial drugs, occurrence of adverse drug reaction and drug interactions which could impact negatively on anti- malarial treatment safely[10].

According to the study conducted in health institutions in Nigeria, the pattern of anti- malarial drugs prescription did not meet the recommended guidelines. As a result, malaria remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children under five years of age in Nigeria. Most of the early treatments for fever and malaria occur through self-medication with anti-malarial bought OTC from un-trained drug vendors. Self-medication through drug vendors can be ineffective, with increased risks of drug toxicity and development of drug resistance[11-13].

Similarly, the study conducted in Ghana revealed that the level of appropriateness of doses of chloroquine prescribed was generally low. Inappropriate doses of chloroquine prescribed were more prevalent in private than government health care facilities, and among prescriptions containing injections[14].

Despite the Essential drug program in countries, there is some evidence of poor prescribing habits by physicians, including irrational use of drugs; high numbers of drugs per prescription and high use of injectable formulations and antibiotics. Inappropriate prescribing has been identified in many health facilities in developing countries. Irrational use of drugs due to inappropriate prescription can also lead to adverse drug events which cause illness or death[15].

The intensive prescribing of the few drugs available for malaria treatment may result in the development of resistance to these drugs. Increased effort should be made to measure and improve the use of different anti-malarial drugs in Sudan. Because of the problems of drug resistance, the few available anti-malarial and the limited financial ability of those who need these drugs, it is vital to make optimal use of the less available anti-malarial and to ensure rational prescribing, dispensing and use of anti-malarial[16].

The major challenges for implementation of anti-malarial drug policy in Ethiopia were dissemination of the new recommendations to health workers and ensuring acceptance of the new policy, given human resource and financial constraints. Other challenges were the lack of appropriate protocols for monitoring the therapeutic efficacy and safety of chloroquine + sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine[17].

According to MOH, Ethiopia, the high treatment failure rates of chloroquine for the treatment of uncomplicated P.falciparum malaria as documented through a nationwide study conducted in 1997/98, led to a treatment policy change that recommends the use of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine as first line drug for the treatment of uncomplicated P.falciparum malaria and chloroquine for the treatment of P.vivax malaria. At the time of introduction of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine as first line drug, the level of treatment failure observed was about 5%[18,19].

In appropriate, ineffective and insufficient use of drugs commonly occur at health facilities in developing and developed countries. Common types of irrational use of drugs include noncompliance with health works prescriptions, self-medication, over use of injections and use of unnecessary expensive drug[20].

The study will help to know the situation of anti-malaria drugs prescription patterns in Gimbi general hospital and identifies the reasons why anti- malaria drugs fails to cure the disease and the resulting consequences to the patient in order to recommend possible solution based on the finding.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and study period: A hospital based cross-sectional study was conducted at GGH which is found in Gimbi town, Oromia region, West Ethiopia. Gimbi town is located at 441km to the west of Addis Ababa and this town has an estimated total population of 30981 from which, 15716 were males and 15265 were females according to the 2007 census. Gimbi general hospital has different wards which include medical, surgical, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology. The study was conducted from, June 25 to July 25, 2018

Study participants and eligibility criteria: All complete prescription cards of anti-malarial drugs of the outpatients in the Gimbi general hospital, who was visit the hospital in the last two years from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018 were included whereas incomplete prescription cards of anti-malarial drugs were excluded.

Study Variables: Independent variables includes Socio demographic characteristics like age, sex, weight and type of plasmodium species whereas dependent variable includes dosage regimen, route of administration, anti- malarial drug combination and prescription pattern.

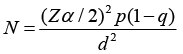

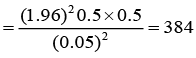

Sample Size determination and Sampling Techniques: The required sample size for study was calculated by using the simple population proportion formula by considering 50% proportion of outpatients with prescribed anti-malarial drugs to get maximum sample size.

Where;

N = sample size

P = an estimate of proportion of outpatients with prescribed anti-malarial drugs = 50%

Z = is standardized normal distribution value at the 95% CI: 1.96

d = the margin of sample error tolerated = 5%

A systematic random sampling was used to select study subject and individual outpatient prescriptions card was chosen at regular interval

Data collection process and management: Data was collected using questionnaire which was developed after reviewing different literature. All selected complete outpatient prescription cards of malaria was reviewed after its completeness were checked. Five percent of the sample was pre-tested to check acceptability and consistency of data collection tool two weeks before the actual data collection.

Data processing and analysis: The data was entered in to computer using EPI-manager 4.0.2 software. Data checking and cleaning was done by principal investigator on daily basis during collection before actual analysis. Analysis was done using statistical software for social sciences (SPSS) 24. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse data in terms of frequency and percentage. The result was presented using tables.

Operational definitions

Anti-malarial drugs: Are drugs used to prevent or cure malaria disease.

Brand name: Is a name chosen by the manufacturer or distributor to facilitate the recognition and association of the product with a particular form for marketing purpose.

Generic name: Is the drug official or common name regardless of who manufactures.

Prescribing practices: Can be defined as the ability of health professionals to differentiate and discriminate among the various choices of drugs and to determine the need of therapy that could be most beneficial to their patient.

Inappropriate use of anti-malarial drugs: Includes prescribing with inappropriate dose, frequency and duration.

Irrational prescribing: Prescribing of drugs in inadequate, excessive or unreliable drug to the disease.

Rational drug use: When patients receive the right drug, at the right dosage, with the right information and the right time.

Rational prescription: A prescription indicating the data of prescription, name, dosage form, strength, dose, frequency, route of administration, the quantity of medical product to be supplied, the name and address of patient, name, sign, address and qualification of the prescriber.

Treatment protocol: Indicate systematically developed statements to help practitioners or prescribers make decisions about appropriate treatment for specific clinical conditions.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

From the total of 384 patients card assessed, 180(46.9%) were female and 204(53.1%) were male. The age distribution shows that the most affected group by malaria was children under the 15 years, 119(31%). The least affected groups were patient above 65 years accounting 8(2.1%) (table1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic distribution of malaria patients in Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

204 |

53.1 |

|

Female |

180 |

46.9 |

|

|

Age( year) |

< 15 |

119 |

31 |

|

15-24 |

101 |

26.3 |

|

|

25-34 |

70 |

18.2 |

|

|

35-50 |

70 |

18.2 |

|

|

51-65 |

16 |

4.2 |

|

|

> 65 |

8 |

2.1 |

|

|

Weight(kg) |

< 5 |

0 |

0 |

|

5-15 |

7 |

1.8 |

|

|

15-25 |

60 |

15.6 |

|

|

25-35 |

46 |

12 |

|

|

>35 |

271 |

70.6 |

|

Types of malaria parasite and commonly prescribed anti-malarial drugs

Concerning the types of parasites, about 263(68.5%) were P.falciparum, 85(22.1%) were P.vivax and the remaining 36(9.4%) were mixed episode of P.falciparum and vivax. As the study indicated, P.falciparum were the most common malarial species in this study area. The result of the study showed that the most commonly prescribed anti-malarial drugs were coartem 290(66.2%) followed by chloroquine 91(20.8%) (table2).

Table 2: The most commonly prescribed anti-malaria drugs at Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018

|

Anti-malarial drug |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Coartem |

290 |

66.2 |

|

Chloroquine |

91 |

20.8 |

|

Primaquine |

43 |

9.8 |

|

Artesunate |

14 |

3.2 |

|

Total |

438 |

100 |

Route of administration of anti-malarial drugs

Concerning the route of administration of anti-malarial drugs prescribed, about 424(96.8%) of drugs were administered orally and 14(3.2%) of drugs were administered by parenteral. The only parenteral administered drug was artesunate (table 3).

Table 3: Route of administration of anti-malarial drugs at Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018

|

Anti-malarial drugs |

Routes of administration |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Coartem |

Oral |

290 |

66.20% |

|

Parenteral |

0 |

0% |

|

|

Chloroquine |

Oral |

91 |

20.80% |

|

Parenteral |

0 |

0% |

|

|

Primaquine |

Oral |

43 |

9.80% |

|

Parenteral |

0 |

0% |

|

|

Artesunate |

Oral |

0 |

0% |

|

Parenteral |

14 |

3.20% |

Prescription pattern of anti-malarial drugs

From the total of patient card reviewed, about 32(8.3%) were prescribed anti-malarial drugs only. The remaining prescribed anti-malarial with antibiotic 77(20.1%), anti-malarial with analgesics 141(36.7%), anti-malarial with both analgesics and antibiotic 129(33.6%) and anti-malarial with others 5(1.3%).

Among the study population, the most commonly prescribed antibiotic and analgesics were amoxicillin 58(12%) andparacetamol 144(29.8) respectively whereas the least prescribed antibiotics and an analgesic were cotrimoxazole 6(1.2%) and ibuprofen 16(3.3%) respectively. (table 4).

Table 4: Most co-administered drugs with anti-malarial agents in malaria infected patients at Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018

|

Drugs co-adminsteredwith anti-malarial |

List of drugs |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Group of drugs |

Antibiotics |

201 |

41.5 |

|

|

Analgesics |

278 |

57.5 |

||

|

Others** |

5 |

1 |

||

|

Total |

484 |

100 |

||

|

Individual |

Antibiotics |

Amoxicillin |

58 |

12 |

|

Doxycycline |

55 |

11.4 |

||

|

Chloramphenicole |

35 |

7.2 |

||

|

Cefalexin |

9 |

1.9 |

||

|

Cotri-moxazole |

6 |

1.2 |

||

|

Ciprofloxacillin |

38 |

7.8 |

||

|

Analgesics |

Paracetamol |

144 |

29.8 |

|

|

Diclofenac |

118 |

24.4 |

||

|

Ibuprofen |

16 |

3.3 |

||

|

Other drugs*** |

5 |

1 |

||

|

Total |

484 |

100 |

||

Note: ** Includes anti-parasite, anti-viral and anti-fungal agents

***Includes mebendazole, aciclovir and ketoconazole

Prescribed names of anti-malarialdrugs

From the total 438 of anti-malarial drugs prescribed 288(65.8) were prescribed by brand name and 150(34.2%) were prescribed by generic names. Coartem was most commonly prescribed by brand name whereas chloroquine was most commonly prescribed by generic names (table 5).

Table 5: Individual anti-malarial drugs prescribed in different names in Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018.

|

Individual drugs |

Names of prescription |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Coartem |

Brand |

288 |

65.7 |

|

Generic |

2 |

0.5 |

|

|

Total |

290 |

100 |

|

|

Chloroquine |

Brand |

0 |

0 |

|

Generic |

91 |

20.8 |

|

|

Total |

91 |

100 |

|

|

Primaquine |

Brand |

0 |

0 |

|

Generic |

43 |

9.8 |

|

|

Total |

43 |

100 |

|

|

Artesunate stat |

Brand |

0 |

0 |

|

Generic |

14 |

3.2 |

|

|

Total |

14 |

100 |

|

|

Total |

438 |

100 |

|

Rational prescribing of dosage regimen of anti-malarial drugs

From patients card reviewed, about 290(75.5%) of the doses was appropriately prescribed and the remaining 94(24.5) was inappropriately prescribed (under dose and over dose). Regarding the frequency and durations about 301(78.4%) and 304(79.2%) of them were prescribed appropriately, respectively (table 6).

Table 6: Appropriateness of dosage regimen of overall anti-malarial prescribed in of Gimbi general hospital from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2018

|

Dosage regimens |

Anti-malarial prescribed |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Dose |

Appropriate |

290 |

75.5 |

|

|

Inappropriate |

Under dose |

67 |

17.5 |

|

|

Over dose |

27 |

7 |

||

|

Frequency |

Appropriate |

301 |

78.4 |

|

|

Inappropriate |

Less frequent |

4 |

1 |

|

|

More frequent |

79 |

20.6 |

||

|

Duration |

Appropriate |

304 |

79.2 |

|

|

Inappropriate |

Shortened |

75 |

19.5 |

|

|

Prolonged |

5 |

1.3 |

||

Discussion

P.falciparum were the most dominant parasite in our study area that covers about 68.5% which was greater than study done in united kingdom in 2013[21] and those done in Basavesh war teaching and general hospital in Gulbarga, India, which accounts 33.1%[22]. However, it was lower than the study done in Gondar, which was 71.2%[24]. When prevalence of both P.vivax and P.falciparum were compared, the prevalence of P.vivax was higher than p. falciparum in study done in India which covers about 60.1%, which was opposite to our study area [22].

The results of the study indicated that, malaria was varying with any sex preferences. It commonly more prevalent in male than female which was similar with study done in Gulbarga general hospital, Nigeria and Gondar[22,23,24].

Concerning commonly prescribed anti-malarial agents, Coartem (Artemether and lumefantrine) had the most prescribing rate 290(66.2%) and Chloroquine was the second 91(20.8%) which was great different from the study held in united kingdom[21] in which 75% patient prescribed artisunate,15% Primaquine and 10% Chloroquine. Furthermore it was also different as compared to the study done in India[22] that prescribed 45.5% of Artesunate, 23.5% of Primaquine, 18.3% of Chloroquine, 5.2% of Coartem and 3.5% of quinine. However when compared to study done in Gondar[24], the Coartem (63.3%) was more commonly prescribed than other anti-malarial drug which was similar to this study. The difference of these anti-malaria drugs, were due to the difference in types of malaria species prevalence and unavailability of more drugs at the Gimbi general hospital.

With respect to percentage of anti-malarial combination, only 77 (20.1%) of the total prescriptions contained anti-malarial and antibiotic combination. This result was more than the study done in Gondar, which was 11.4%[24], due to experience of health professionals towards the drugs.

Regarding percentage of anti-malarial and analgesics combinations, it was higher 141(36.7%) than other drugs combinations. This result is lower when compared with the study done in Nigeria, which was 41.1%[23], due symptom to the patients.

Concerning the percentage of anti-malarial drugs prescribed by generic and brand names, 34.2.0% was prescribed by generic and the remaining 65.8% was prescribed by brand names. This was higher when compared to the percentage of anti-malarial drugs prescribed by generic names in India which was 2.6%[22]. This is due to in our study there was high supply of generic drugs by governments. However, the result of the study was nearly similar with the study done in Gondar, which was 32%[24], due to the voluntary of physician or health workers to write the generic names of the drugs. The appropriateness of anti-malarial drugs prescribed was lower than the study conducted in selected health facilities of Jimma zone which was 85%[26]. This is due to, in our study there was few clinical pharmacist assigned to that hospital.

Conclusion

P.falciparum was the most common parasite diagnosed in Gimbi general hospital followed by P.vivax where as coartem was the most commonly prescribed anti-malarial agent followed by chloroquine. Among the patient card reviewed, the most commonly prescribed anti-biotic and analgesics were amoxicillin and paracetamol respectively. The least prescribed antibiotics and an analgesic was cotrimoxazole and ibuprofen.

From the total card reviewed, about three-fourth of them was prescribed with appropriate dose and the remaining one-fourth was inappropriately prescribed (under dose and over dose). Therefore Presence of clinical pharmacist plays pivotal role in order to facilitate and promote appropriate use of drugs by intervening different problems in prescribing, dispensing and providing necessary advices for the patients and health professionals regarding the overall issues related to drugs and the hospital should have sufficient types of anti-malarial drugs according to updated guidelines.

Limitation

As limitations, the study was cross-sectional and the causal effect relationship cannot be found and incomplete information of patient cards. The study was not a multicentre so that it lacks better representativeness to other areas.

Acknowledgement

We thank Wollega University for funding this study. We are grateful to staff members and health care professionals of GGH, data collectors and study participants for their cooperation in the success of this study.

Authors’ Contributions

FB contributes in the proposal preparation, study design, analysis and writes up the manuscript. DD contributed to the design of the study and KB contributed to analysis. ST contributed to edition of the manuscripts. TT made a substantial contribution to the local implementation of the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent-to-Participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethics review board of Wollega University. Permission was obtained from medical director of the GGH to access malarias patients and conducts the study. The benefit and risks of the study was explained to each participant included in the study and written consent were obtained from each patient involved in the study. To ensure confidentiality, name and other identifiers of patients and health care professionals were not recorded on the data collection tools.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. No individual person’s personal details, images or videos are being used in this study.

Funding

The study was funded by Wollega University. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and / or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

No competing interests exist.

References

- 1. Malaria, centers for disease control and prevention. (2013) World health organization.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 2. Filler S, Causer LM, Newman RD et al., Malaria surveillance, United States, 2001. (2003) MMWR Surveillance Summ 52: 1-14.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 3. Owusu-Ofori AK, Betson M, Parry CM et al., Transfusion transmitted malaria in Ghana. (2013) Clin Infect Dis 56(12): 1735-1741.

- 4. Malaria. (2014) World health Organization.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 5. World malaria report. (2011) World health organization.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 6. Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS et al., Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. (2012) Lancet 379(9814): 413-431.

- 7. Malaria: Canters for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 8. Etuk EU, Egua MA and Muhammad AA.Prescription pattern of ant malarial drugs in children Under 5 years in a tertiary health institution in Nigeria. (2008) 7(1): 242.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 9. Omole MK and Onademuren OT. A Survey of anti- malarial Drug Use Practices among Urban Dwellers in Abeokuta, Nigeria. (2010) Afr J Biomed Res 13: 1-7.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 10. Gogtay, N.J., Kadam, V.S., Desai, S., et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of three anti-malarial treatments for acute, uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mumbai. (2003) J Assoc Physicians India 51: 877-879.

- 11. Hanson, K., Goodman, C., Lines, J., et al. The economics of malarial control.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 12. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Essential drugs and medical supplies policy.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 13. Okeke,T. A., Benjamin, S.C. Uzochukwu, Improving childhood malaria treatment and referral practices by training patent medicine vendors in rural south-east Nigeria. (2009) Malar J 8: 260.

- 14. Abuaku, B. K., Koram, K. A., Binka, F. N. Anti-malarial Prescribing Practices: A challenge to Malaria Control in Ghana. (2005) Med Princ Pract 14(5): 332-337.

- 15. Akande, T.M., Ologe, M.O.. Prescription pattern at a secondary health care facility in Ilorin, Nigeria. (2007) 6(4): 186-189

- 16. Yusuf, M.A., Adeel, A.A. anti- malarial prescribing patterns in Gezira State: precepts and practices. (2000) EMJH 6(5-6): 939-947

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 17. The use of anti- malarial drugs: anti- malarial treatment policies

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 18. Federal Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of health, Malaria Diagnosis and Treatment.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 19. Action programmer on essential drugs and rational use. (1988) WHO.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 20. Arusiyona promoting rational use of drugs in Indonesia. (1999).

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 21. Vanaja, K., Priyanka, N., JahurulHlaq, G., et al. Drug utilization study of anti- malarial drugs. (2013) United Kingdom Ireland.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 22. Shantveer, H. C., Neelkantreddy, P., Hinchageri, S.S., et al. Analysis of prescription pattern of anti- malarial and its cost in malaria at teaching hospital. (2012) Int J Pharmacol Ther.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 23. Martin, meremikwu., uduak, O., Joseph, O., et al. descriptive study on anti- malarial drug of prescribing practice in private and public health facilities in south east Nigeria. (2003).

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 24. Atnafu, T., Baye, B., Mokennen, B. Assessment of anti-malarial drug prescription pattern in koladiba health center in north Gondar, Ethiopia. (2014).

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 25. Ketema, T., Bacha, K., Birhanu, T., et al. Chloroquine resistant by Plasmodium vivaxmalaria. (2009) Jimma South west Ethiopia.

Pubmed| Crossref| Others

- 26. Tessema, A. T., Ayanen, A. T., Wabe, N.T. Indicator- based assessment on anti-malarial drug availability and utilization among selected public health facilities in south-west Ethiopia. (2012) Therapeutic innoviation regulatory sci