Sudden Onset Bilateral Lower Limb Weakness in a Young Female Patient After a Long Haul Flight

Asadi H*, Sheehan M, Brennan P, O’Hare A, Thornton J, Looby S

Affiliation

1Department of Radiology, Neuroradiology and Neurointerventional Service, Beaumont Hospital, Beaumont Road, Beaumont, Dublin,Ireland

2School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Pigdons Road, Waurn Ponds, Australia

Corresponding Author

Asadi H, Interventional Radiology Service, Department of Radiology, Beaumont Hospital, Beaumont Road, Beaumont Dublin 9, Ireland, Tel: +35318093000; Fax: +3531809837 6982; E-mail: asadi.hamed@gmail.com

Citation

Asadi H., et al. Sudden Onset Bilateral Lower Limb Weakness in a Young Female Patient after a Long Haul Flight. (2016) Int J Neurol Brain Disord 3(1): 1-3.

Copy rights

© 2016 Asadi, H. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

ASCIS; Spinal; Infarction; MRI; b-value

Abstract

In this article we present a case of sudden onset bilateral lower limb weakness in a young female secondary to an acute spinal cord infraction after a long haul flight. Our case highlights the importance of early recognition of the clinical symptoms and signs associated with this condition and the role of properly optimised diagnostic imaging.

Introduction

Spinal cord infarction or acute spinal cord ischaemic syndrome (ASCIS) is an uncommon pathology but is associated with significant morbidity and a poor prognosis. The most common aetiologies of ASCIS include atherosclerosis, idiopathic, aortic aneurysm, along with patients who have undergone aortic interventions. The clinical presentation varies but the majority of patients develop symptoms early, usually within 12-24 hours[1], including but not limited to motor dysfunction, pain and sensory dissociation. Here we present the case of a young woman who presented with lower limb weakness secondary to ASCIS.

Case Report

A 41-year-old female patient presented with mild thoracic back pain, and sudden onset bilateral lower limb weakness that progressed to a dense paraplegia within 24 hours.

The patient did not have any significant past medical history, and presented a week after a long haul flight with a small child that she carried on her lap on board. The weakness was rapid in onset, with the patient no longer able to weight-bear.

On examination, there was dense bilateral lower limb palsy, with loss of reflexes. Sensation was decreased with a T10 sensory level. There was no convincing upper limb weakness. Proprioception and vibration was preserved. Full blood count, electrolytes, serum protein electrophoresis and cerebrospinal fluid analyses were unremarkable. The patient underwent a MRI of the cord (Figure 1-3).

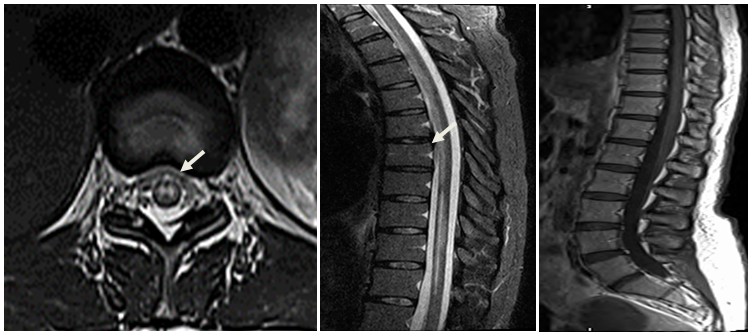

Figure 1: Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted as well as sagittal T1-Postcontrast (C) images, with the abnormality highlighted with the arrow.

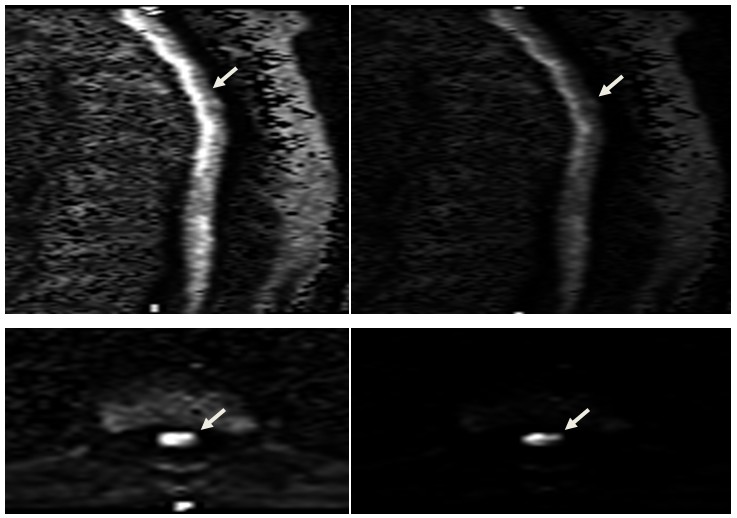

Figure 2: Sagittal and axial thoracolumbar spine diffusion-weighted images with the refined B-value of 1400 s.mm-2, in their native space (A & C) as well as nonlinear gamma corrected format with 230 window and level of 12 (B & D). The abnormal diffusion restriction in the cord is more discernible on the modified imaged (arrows).

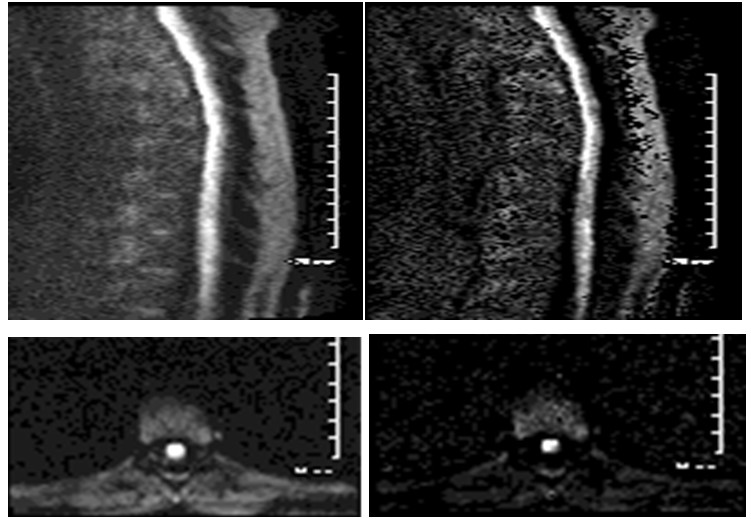

Figure 3: Sagittal and axial diffusion weighted imaging with B-value of 700 s/mm² (A & C), and 1400 s/mm2 (B & D) for comparison.

Discussion

Spinal cord infarction is a relatively rare condition, with the commonest type being anterior spinal artery syndrome, presenting with acute bilateral weakness/paraparesis, impaired spinothalamic sensation and preserved propriception and vibration with or without respiratory dysfunction[2].

Common aetiologies include atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm, aortic surgery, dissection, and hypercoagulabe state. Hence, spinal cord infarction arising by atherosclerotic pathogenesis has a propensity to occur in elderly and vasculopathic patients[2-5]. The classical MRI features of spinal cord infarction are anterior horn T2 hyperintensity without significant cord expansion or contrast enhancement (owl’s eyes sign). Although usually technically difficult to image, if possible, diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates corresponding abnormal restricted diffusion, as in acute cerebral infarction[3].

We experimented with several different B values in order to attain a more diagnostic image. As seen in figure 3 we used diffusion weighted images with ranges from 700s/mm² to 1400s/mm². We were able to obtain the optimal diagnositc image without loss of the background anatomical signal as seen in figure 3 (B&D). A striking abnormal diffusion restriction along the anterior cord which was congruent with decreased signal intensity demonstrated on ADC, was also indicative of an acute ischemic process.

These MRI changes were evident in our case with T2 hyperintensity demonstrated on the sagittal and axial images (Figure 1A, B) which was confined to the grey matter of the cord, consistent with known particular sensitivity of the neuronal perikaryon to hypoxia. Our patient had clinical and radiological findings consistent with diffuse cord infarction, which is an unfortunate condition with a grim prospect of recovery, as it was in this case as well, with no improvement after 3 week[2-6].

Conclusion

In conclusion, ASCIS is a rare pathology that can often be difficult to diagnose confidently with conventional imaging. However we propose that by technical manipulation of the B-value up to 1400s/mm² on a 3T conventional clinical machine (MAGNETOM Skyra - Siemens, Erlangen - Germany) diagnostic image can be attained.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this research and its publication.

References

- 1. Masson, C., Pruvo, J.P., Meder, J.F., et al. Spinal cord infarction: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings and short term outcome. (2004) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75(10):1431-1435.

- 2. Novy, J. Spinal cord syndromes. (2012) Front Neurol Neurosci30:195-198.

- 3. Novy, J., Carruzzo, A., Maeder, P., et al. Spinal cord ischemia: clinical and imaging patterns, pathogenesis, and outcomes in 27 patients. (2006) Arch Neurol63(8):1113-1120.

- 4. Picone, A.L., Green, R.M., Ricotta, J.R., et al. Spinal cord ischemia following operations on the abdominal aorta. (1986) J Vasc Surg 3(1):94-103.

- 5. Tubbs, R.S., Blouir, M.C., Romeo, A.K., et al. Spinal cord ischemia and atherosclerosis: a review of the literature. (2011) Br J Neurosurg 25(6):666-670.

- 6. Sandson, T.A., Friedman, J.H. Spinal cord infarction: report of 8 cases and review of the literature. (1989) Medicine (Baltimore) 68(5):282-292.