Abdominal Distension in a Patient with Hepatitis C-An Unexpected Diagnosis

Haris Baig2, Suimin Qiu3 and Maurice Willis2

Affiliation

- 1Department of internal medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston

- 2Department of Clinical Oncology, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston

- 3Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston

Corresponding Author

Maen, M. Masadeh, Department of Internal Medicine, 301 Universities Blvd, JSA 4.160, UTMB, Galveston, TX 77555-0561, Tel: 3199360074; Fax 409.7474-2369; E-mail: maen_masadeh@hotmail.com

Citation

Masadeh, M.M., et al. Abdominal Distension in A Patient with Hepatitis C – An Unexpected Diagnosis. (2015) Int J Cancer Oncol 2(1): 1-3.

Copy rights

© 2015 Masadeh M.M. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor; Hepatitis C; Imatinib

Abstract

We present a case of a cachectic patient with Hepatitis C without cirrhosis that presented with worsening abdominal distension and weight loss. The patient was initially thought to have decompensated cirrhosis but later found to have unclassified sarcoma. Further workup was done with repeat biopsy and checking for CD117 (c-kit) established a diagnosis of extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor. The patient was started on targeted therapy and had a dramatic response.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are rare tumors, with an estimated incidence of 1.5/100000/year[1]. They are the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract and are highly resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radio therapy[2]. They most frequently occur in the stomach or colon, but about 10% are extra-gastrointestinal and develop in the mesentery, omentum and retroperitoneum[1,3].

The clinical presentation may vary and 20% remain asymptomatic[4,5]. Most patients present with vague symptoms such as early satiety, abdominal pain, and weight loss[6]. Another common symptom may be bleeding which is related to erosion of the tumor into the GI tract lumen[6]. We present a case of extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor in hepatitis C patient that was initially misdiagnosed as ascites and later treated with Imatinib after obtaining adequate biomarkers. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case Presentation

The patient is a forty-two year-old Hispanic male with a history of hepatitis C infection that presented with significant abdominal distension, weight loss and cachexia. He had a 4-month history of an unintentional 60 pounds weight loss and slowly increasing abdominal girth. He went to see his local provider and was found to have abdominal distension (figure 1) thought to be secondary to newly developed cirrhosis and ascites. Basic lab work was done and showed normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 7.3g/dl), normal liver function test, normal coagulation parameters, and borderline low albumin. The patient was started on diuretics without any clinical improvement. His abdomen continued to enlarge to a point causing significant shortness of breath. Due to the concern for decompensated cirrhosis, the patient was sent to another hospital emergency department where he was found to have the same physical exam findings and lab results. The medical provider anchored the diagnosis of ascites and attempted an unsuccessful blind bedside paracentesis despite the evidence of the importance of using ultrasound. A Computed-Tomography of the abdomen(figure 2) was subsequently done which showed a heterogeneous, primarily hypodense mass with scattered areas of increased hypodensity filling the entirety of the peritoneum, sandwiching the bowel and intraperitoneal structures. A biopsy of a peritoneal lesion showed an unclassified sarcoma with myxoid features with some features suggestive of extra-skeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (figure 3). The patient was referred to a tertiary hospital (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston) for further evaluation. Ultrasound guided core biopsy was repeated and showed an extensive myxoid component as well as some epitheloid features. Immunohistochemical stains were similar to the previous biopsy. However, since the tumor was sarcomatous, CD117(C-kit) and DOG-1 were checked and came back positive. His pathology was consistent with an extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor. The patient was started on Imatinib 200mg oral twice daily. The patient's clinical response was dramatic with decrease in abdominal distension, significant weight gain and improved functional capacity.

Figure 1: Physical examination of the abdomen before and after Imatinib.

Before Imatinib (left): Large tense distended abdomen, seen on initial presentation

After Imatinib (right): Soft less dense abdomen 6 months after treatment

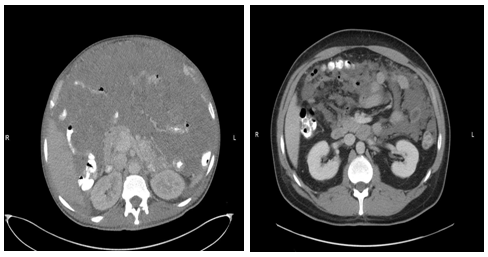

Figure 2: CT scan of the abdomen

Before Imatinib (left): A heterogeneous, primarily hypodense mass with scattered areas of relatively increased hypodensity fills the entirety of the peritoneum, sandwiching the bowel and intraperitoneal structures. This mass limits detailed evaluation of the solid intra-abdominal organs.

After Imatinib (right): Massive response to treatment characterized by decreased in size of peritoneal masses. Organs are now visible

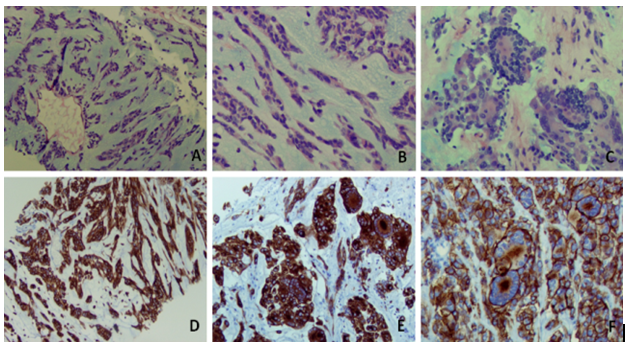

Figure 3: Needle Biopsy

Ovoid to spindle cell component with predominant chondroid-myxoidstroma (Figure A and B). Tumor cells form cords and strands or tumor nests with no glandular component (Figure A and B). Some cells contain intra-nuclear pseudo inclusion or vesicular nuclei. Overall the tumor cells show rare mitosis with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and occasional giant tumor cells with numerous peripheral nuclei (C). Tumor cells are immunohistochemically positive for C-Kit (Figure D and E) and DOG-1 (Figure F) including tumor giant cells.

Discussion

Ascites is a significant complication in cirrhotic patients and occurs in 50% of patients over 10-year follow up[7]. Naturally, when a patient with a history of hepatitis C presents with worsening abdominal distension, physicians consider decompensated cirrhosis with ascites at the top of their differential diagnosis. However, progressively worsening abdominal distension with weight loss and severe abdominal pain may be due to other reasons like GIST.

The identification of genetic alterations for sarcomas including GIST has led to specific therapeutic targets. The tumor can be positive for KIT, S100, DES, Keratin, CD34, and ACAT2[8-10]. Activated KIT or PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha-polypeptide) mutations are identified in over 90% of sporadic GIST(2). KIT is the most specific and sensitive marker, although 5% of tumors are KIT negative[9,11]. Other marker that can differentiate between non-specific sarcoma and GIST is CD34, a hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen. However, CD34 is also present a wide variety of fibroblastic and endothelial tumor cells[10].

Mutations in the KIT oncogene result in a ligand-independent activation of the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase pathway which ultimately leads to a number of cellular responses which affects cell division, adhesion, chemotaxis, and apoptosis[2]. A major clinical advance had been driven by the recognition of activating KIT mutations in the pathogenesis of GIST[9]. Imatinib has been found to act as a selective inhibitor of tyrosine kinase of the c-kit receptor and PDGFR. There have been multiple studies done on imatinib showing the efficacy on GIST. Imatinib reliably achieves control in 70-85% of patients with advanced GIST with median progression free survival of 20-24 months[11]. Median overall survival with Imatinib exceeds 36 months in large clinical studies[12-14].

In summary, this was a patient who presented initially with the picture of decompensated cirrhosis. On further workup he was found to have sarcoma with extensive myxoid features and some features of extra-skeletal chondrosarcoma. The prognosis of the patient was considered poor given the patient's poor performance status, large tumor burden that compressed vital abdominal organs, and poor surgical candidacy. The fact that c-kit was positive made a major change in the outcome and allowed using targeted therapy.

Conclusion

Although ascites is a possible diagnosis when evaluating a patient with abdominal distention and history of chronic hepatitis, but other etiologies should be considered. Anchoring bias is common and usually delays treatment. Moreover, when a patient is found to have a non-specific gastrointestinal related sarcoma, one should always consider checking c-kit as it can mean the difference between life and death.

References

- 1. Casali, P.G., Blay, J.Y., ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Experts. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. (2010) Ann Oncol Suppl 5: v98-102.

- 2. Rubin, B.P., Singer, S., Tsao, C., et al. KIT activation is a ubiquitous feature of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. (2001) Cancer Res 61(22): 8118-8121.

- 3. Reith, J.D., Goldblum, J.R., Lyles, R.H., et al. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. (2000) Mod Pathol 13(5): 577-585.

- 4. Heinrich, M.C., Corless, C.L., Duensing, A., et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. (2003) Science 299(5607): 708-710.

- 5. Kim, K.M., Kang, D.W., Moon, W.S., et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Koreans: it's incidence and the clinical, pathologic and immunohistochemical findings. (2005) J Korean Med Sci 20(6): 977-984.

- 6. Stamatakos, M., Douzinas, E., Stefanaki, C., et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. (2009) World J Surg Oncol 7: 61.

- 7. Ginés, P., Quintero, E., Arroyo, V., et al. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. (1987) Hepatology 7(1): 122-128.

- 8. Kindblom, L.G., Remotti, H.E., Aldenborg, F., et al. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. (1998) Am J Pathol 152(5): 1259-1269.

- 9. Fletcher, C.D., Berman, J.J., Corless, C., et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. (2002) Hum Pathol 33(5): 459-465.

- 10. Sarlomo-Rikala, M., Kovatich, A.J., Barusevicius, A., et al. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. (1998) Mod Pathol 11(8): 728-734.

- 11. Rubin, B.P., Heinrich, M.C., Corless, C.L. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. (2007) Lancet 369(9574):1731-1741.

- 12. Heinrich, M.C., Corless, C.L., Demetri, G.D., et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor.(2003) J Clin Oncol 21(23): 4342-4349.

- 13. Blanke, C.D., Rankin, C., Demetri, G.D., et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. (2008) J Clin Oncol 26(4): 626-632.

- 14. Verweij, J., Casali, P.G., Zalcberg, J., et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. (2004) Lancet 364(9440):1127-1134.